Survivor experience: Wiremu Waikari Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Wiremu Waikari

Hometown Te Oreore Masterton

Age when entered care 11 years old

Year of birth 1954

Type of care facility Family homes – Workshop Road Family Home; foster homes; girls’ home – Miramar Girls’ Home in Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington; boys’ homes – Epuni Boys’ Home in Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Lower Hutt, Hokio Beach School near Taitoko Levin, Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre in Taitoko Levin; borstal – Invercargill Borstal in Waihopai Invercargill.

Ethnicity Māori (Ngāti Porou)

Whānau background Wiremu was raised by his uncle in a whāngai arrangement until he was 7 years old. He then lived with his mother, brother and a cousin before going into care at 11 years old.

Currently Wiremu is a social worker and has degrees in social science and counselling therapy. He and his partner work together in education and coaching people who are facing trauma. Wiremu is a grandfather.

Being placed into care meant the trajectory of my life changed drastically. I’m lucky that I survived it.

When I was 1 year old my mother gave me to my maternal uncle through the practice of whāngai. I had a happy childhood on a farm, immersed in Māori culture. When I was young, I was hit in the eye with a dart – I was declared legally blind in 1984 while in prison. I believed my adoptive parents were my real parents until, at 7 years old, my uncle gave me back to my mother. I think it was because I was very sick with eczema and asthma.

I first came to the attention of social welfare after appearing in the Children’s Court on charges of burglary and theft. My mother tried her best but I was confused and angry – she was like a stranger to me. I would run away back to my uncle’s. At age 11 years old, I was placed in a family home. Then I was at various places including Epuni Boys’ Home twice. When I was 13 years old I was transferred to Hokio Beach School.

On the third night at Hokio, me and two other boys got a ‘welcome’ beating. Afterwards I was bleeding from the nose and mouth. I knew it was coming, so I was glad it was over. I experienced and witnessed physical violence and intimidation from staff and other boys almost every day. Some of the bigger boys knocked me out a few times.

By the time I got to Hokio, ‘no narking’ was thoroughly ingrained into me and I knew not to complain to anybody about the beatings. This was just as well, because I witnessed many boys being beaten for narking. Often, the younger, newer boys would take a while to figure out the hierarchy of boys, with the kingpin at the top, and would be beaten for narking to staff.

Another staff member set up fights in the gym a lot. It was said he was teaching us to defend ourselves, but what he taught me is that you settle matters with your fists. If you look back through my criminal record, you’ll see that’s exactly what I did.

One housemaster, who was ex-military, regularly punished me by making me run, duck walk and leapfrog around a huge field. He screamed and yelled at me like a drill sergeant, and repeatedly thrashed my legs, back and shoulders with a stick. He emotionally abused me, saying I was a “useless fucking black bastard”.

The female nurses also sexually abused the boys. One nurse lived on site and she got me and another guy to go over to her house a lot. We weren’t having penetrative sex with her, but we were masturbating and playing with her. There was no way we thought that this behaviour was abusive at only 13 years old. I had no idea. Hokio was where I first learnt about gangs. I also learnt a lot about crime. A few of the housemasters tried to teach us right from wrong, but many did not.

I was sent to the secure unit at Kohitere as punishment for converting a car. It was like a real jail – everyone was yelling and you got hit if you didn’t move like they wanted you to. The cell was hosed down at about 5am each day. I was forced to perform excessive physical training, which involved push-ups, medicine balls and sit-ups. I was placed in the secure unit at Kohitere another time for breaking into a staff member’s house and drinking their alcohol. On several occasions during this stay I was denied food.

I was officially admitted to Kohitere five months after that. I was in secure for about a month before I was let out into the main residence. Kohitere was different from anywhere because there weren’t any boys there, most of them were young men. I was 14 years old at this stage, but I was quite hardened – I was fit and strong. I received my initiation beating the first night. It was the expected routine so I knew that was coming. I had a blanket thrown over me and was punched and kicked by other boys. I was repeatedly hit with a pillowcase filled with heavy objects.

On several occasions, staff were present when other boys assaulted me but they did nothing. I frequently witnessed boys being beaten and stomped on by other boys and staff. Staff members also forced boys to fight each other. I was beaten, kicked and punched by boys on the command of staff members. I was also verbally abused. It became standard, that was just the way that we were treated and spoken to.

I was aware of sexual abuse perpetrated on younger, smaller boys. This involved forcing boys to perform oral sex and forced anal penetration of some boys with a broom. I was told boys performed oral sex in exchange for cigarettes and chocolate.

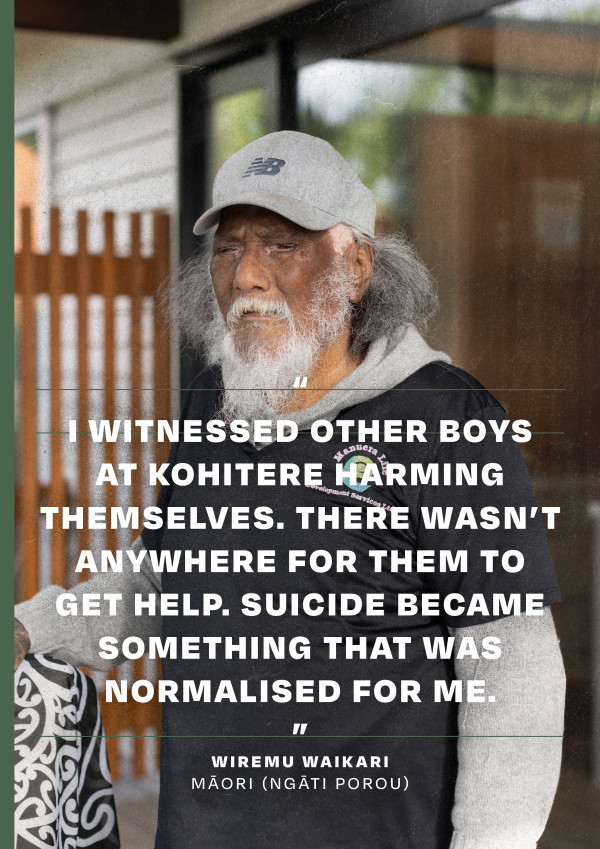

I witnessed other boys at Kohitere harming themselves. There wasn’t anywhere for them to get help. Suicide became something that was normalised for me – it happened so often that I just began to accept it when people would disappear.

I had minimal education while at Kohitere, but instead I was exposed to and learnt about criminal conduct and activities from other residents on a daily basis, without intervention from staff members who were often present when criminal conduct was discussed.

It was the links I made in Hokio and Kohitere that led me to joining the Mongrel Mob when I was 16 years old. I loved it because I already knew them – I felt more at home with Mob members than I did with my own family.

In the 1960s and 1970s, gangs in New Zealand really kicked off because the boys’ homes were feeding them with disenfranchised young people who were not nurtured by Māori or the State. That is definitely where my time in State care pushed me, and hundreds of other unhappy Māori kids, who weren’t sure of themselves in any world.

While in prison, I left the Mob and on my release trained to be a social worker. I like to provide a cultural element, that is the most important thing to me. As a social worker, I sit directly with my people on a day-to-day basis. I witness the ongoing issues that my people face within the current systems and I understand how the systems must be changed.

I have done a lot of bad things, I have hurt a lot of people, shed a lot of blood. I’m fortunate because I’m quite happy with where I have got to in life – I can use my experiences to help others. Now I’ve got all these mokos to look out for and I don’t want them to run into the same problems. I want them to have a chance.[66]

Footnotes

[66] Witness statement of Wiremu Waikari (27 July 2021).