Chapter 3: Nature and extent of abuse at Hokio School and the Kohitere Centre

34. Hokio Beach School (Hokio School) and Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre (Kohitere Centre) were places of extreme sexual and physical abuse and described by survivors as the worst of the boys’ social welfare institutions. Violence was normalised and perpetrated and incited by staff. Survivors described the two places as “a hellhole”[67], a ‘nightmare’[68], ‘terrifying’[69], “absolute unbelievable shit”[70], ‘horrendous’[71], “sadistic torture”[72], “run on terror”[73], and places where you would “wake up in fear and go to bed in fear”.[74] Many survivors experienced a lack of formal schooling and Māori and Pacific survivors said they had little access to their culture or language while in care. Although many survivors from Kohitere received trades training, some said it felt like slave labour.

35. The staff at Kohitere and Hokio consistently used secure as a form of punishment and control, which was a breach of the regulations. Staff also used excessive physical training, often coupled with violence as a way to punish boys. NZ European survivor Mark Goold described the Kohitere Centre staff: “They were called housemasters, but they were really screws.”[75] NZ European survivor Darren Knox described Kohitere Centre an evil “cauldron of hatred”.[76]

36. This chapter describes the nature and extent of abuse at Hokio School and the Kohitere Centre during the Inquiry period.

Survivors experienced physical abuse

37. According to the Inquiry’s analysis of Ministry of Social Development data, physical abuse was the most common kind of abuse experienced, and for some the abuse was almost daily. Most people who made a claim to the Ministry of Social Development's Historic Claims unit said they were physically abused (90 percent for Hokio School and 92.5 percent for Kohitere Centre).[77] Sixty-seven percent of survivors from Hokio School and Kohitere Centre who spoke to the Inquiry reported physical abuse from their peers compared to 55 percent reporting abuse from staff.[78] However, historic claims data shows that more survivors from both settings had far more claims of physical abuse against staff.[79]

Survivors experienced extreme physical abuse from staff members

38. Survivors experienced physical abuse from staff, including being punched,[80] slapped,[81] kicked,[82] dragged,[83] put into headlocks,[84] thrown into walls,[85] and stomped on.[86] One survivor from Kohitere Centre told the Inquiry a staff member choked him until he was unconscious.[87] Another survivor told the Inquiry he was hit so hard by a teacher at Hokio School that his ear drum burst.[88] Another survivor still experiences pain at the site of an arm fracture, from being tackled by a Hokio School staff member.[89]

39. Corporal punishment was permitted until 1986 and could only be administered by the principal or vice-principal. However, survivors reported being strapped by other staff members, and said the corporal punishment they received was excessive. It went far beyond what they believed would be permissible.[90] NZ European survivor Mr JM said one staff member at Kohitere Centre would strap them on their genitals.[91] Survivors also told the Inquiry of staff assaulting them with weapons, including bundles of keys,[92] sticks,[93] belt buckles,[94] bats,[95] a shovel,[96] and a two-by-four plank.[97]

40. Some staff members who felt disrespected or upset by boys responded with physical abuse.[98] Italian Māori survivor Tyrone Marks (Ngāti Raukawa) described a staff member at Hokio School:

“Whoever made him mad knew they were going to suffer for it. This man was scary and had a voice that matched his temper. I saw him going nuts at boys quite a bit.”[99]

41. Survivors said that staff who were ex-military liked to intimidate and beat up the boys. Māori survivor Paora (Paul) Sweeney (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Hako) described a Kohitere Centre staff member:

“He came out of the Army … He beat me in a way that there was no marks. He beat me with headlocks, twisting my arms and squeezing my neck until I'd be screaming.”[100]

Survivors experienced excessive physical training and other harsh punishments

42. Children and young people were subjected to extreme physical ‘training’ (PT) as punishment. This often took place while they were being held in the secure wing. Māori survivor Wiremu Waikari (Ngāti Porou) told the Inquiry that he was “forced to perform excessive PT, which involved push-ups, medicine balls and sit ups” and that this occurred repeatedly throughout the day.[101]

43. Several former staff members spoke about the use of physical training at Hokio School. One said the use of the ‘coldie bar’ where boys had to hold a netball pole over their shoulders and run around was ‘inappropriate’.[102] Another described the physical training as “gruelling and tedious” and, at times, excessive.[103]

44. Children and young people at Kohitere Centre were also forced to do physical training, often when they were being held in the secure facilities. Survivors also described being abused during physical training.[104] Sometimes this was because they were too exhausted to keep going.[105] NZ European survivor Mr GZ described his punishment after attempting to run away:

“I was made to do PT [personal training] naked. This involved me running laps around the block, still completely naked, every 10th lap you would do push-ups in the middle of the yard. Every time I ran past Mrs [staff member], she would hit me with a metal hearth shovel ... ”[106]

45. Staff would sometimes try and justify the personal training as a deterrent from further unwanted behaviour. A principal of Kohitere Centre in the 1970s wrote to the superintendent of the Child Welfare Division describing a “crash get fit programme” for a group of returned children and young people who had attempted running away in secure care. His rationale was that the intense physical exercise would “make them think twice before repeating the performance”.[107]

46. Survivors were also punished in other ways. One survivor described being forced to clean a toilet full of faeces with his bare hands while a staff member stood over him. He threw up and was unable to continue so was “repeatedly hit around the head”.[108] NZ European survivor Desmond Hurring told the Inquiry:

“Punishments included having to watch other boys eat when I was not given any food, shovelling coal, being forced to run around the buildings, washing dishes for a week, losing smoking privileges, scrubbing pig bins, washing staff cars, and scrubbing the floors and stairs.”[109]

47. Survivors from Hokio School also described an extreme form of punishment where they were made to move sand around the sand dunes.[110] NZ European survivor Mr UD told the Inquiry he was made to do this as a punishment for bed wetting.[111] A former principal admitted to the use of this punishment.[112]

Survivors experienced initiation beatings from other boys

48. Many survivors described being subjected to initiation beatings within their first few days.[113] About 40 percent of the survivors who spoke to the Inquiry experienced this.[114] These beatings were perpetrated by a group of boys, usually at night, and out of sight of the staff. They were sometimes referred to as ‘blanketings’ or ‘stompings’, as survivors would be covered by a blanket or put inside a bag and be beaten and stomped on.[115]

49. Some survivors knew what to expect as they had gone through this at other boys’ homes but said that at Hokio School and Kohitere Centre it was worse. Survivors told the Inquiry it was particularly bad at Kohitere Centre because of the age and size of the boys.[116] Māori survivor Daniel Rei (Ngāti Toa Rangatira) described his first night at Kohitere Centre:

It was like adult-scale fighting with full-on punches. I suffered superficial injuries: cuts, scrapes, black eyes, a scraped face and so on. It was a familiar scenario in that the pack attack seemed to be part and parcel of anything new.”[117]

50. Survivors told the Inquiry that these beatings were normalised and the expectation was that they would eventually do this to new boys coming into the home. Māori survivor Wiremu Waikari (Ngāti Porou) said: “It was a sick cycle of violence.”[118]

51. The Inquiry heard that staff were aware of these beatings but did not step in. A residential social worker at Hokio School in the late 1970s described two admission procedures: a formal procedure where staff inducted children and young people and “the informal initiation ... [at] the back of the sand hills”.[119] Several staff members from Kohitere Centre also acknowledged that ‘stompings’ and initiation beatings took place.[120]

Survivors experienced bullying and violence among the boys

52. Survivors described a culture of extreme violence and bullying between the boys at both institutions. Italian Māori survivor Tyrone Marks (Ngāti Raukawa) told the Inquiry: “The bullying at Hokio was far more severe than it had been at the earlier institutions. The boys at Hokio were more aggressive and it was overall a more violent place.”[121] Some survivors described a ‘kangaroo court’[122] at Kohitere Centre where they were forced to move down a corridor while other boys would throw punches or objects at them.[123]

53. Māori survivor Daniel Rei (Ngāti Toa Rangatira) told the Inquiry:

“Boys would urinate, and even shit in my bed. They all thought it was funny. I would just wake up to find somebody urinating on me. One time I even awoke to find a boy ejaculating on me.”[124]

54. Weaker, smaller and more effeminate boys were often the targets for abuse.[125] Māori survivor Mr FI (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Porou) was 11 years old when he went to Hokio School and described being constantly abused by the older boys. He was ‘king hit’[126] and the impact almost fractured his skull.[127]

55. There was a strong kingpin culture at Hokio School and Kohitere Centre and everyone knew their place within the hierarchy.[128] At Kohitere Centre, boys had different names depending on their place within the hierarchy. ‘Spankers’ were at the bottom and then it moved to ‘New Boy’, ‘K-Boy’, ‘Old Boy’, and the kingpin at the top.[129] The principal of both Hokio School and Kohitere Centre said he believed kingpins had a good influence.[130]

56. Staff condoned and even organised fights between the boys.[131] Māori survivor Wiremu Waikari (Ngāti Porou) described one staff member who did this:

“These fights were full-on violent fights until one boy gave up or was knocked out. Some of the fights were short, some were long and lasted about 15 to 20 minutes. Some were bloody affairs. Mr Paurini would watch and directly encourage the boys to fight.”[132]

Survivors experienced sexual abuse

57. Sexual abuse was perpetrated by staff and other children or young people. This could be a one-off event or happen multiple times, from multiple perpetrators. According to the Inquiry’s analysis of historic claims data provided by the Ministry of Social Development, there were 124 allegations of sexual abuse at Hokio School and 135 at Kohitere Centre.[133] The number for Hokio School is remarkably high, given it had half the children and young people of Kohitere Centre.

Sexual abuse by staff happened across the decades

58. Around one third of registered survivors who spoke to the Inquiry from Hokio School and Kohitere Centre described sexual abuse from staff from the 1950s to the 1980s.[134] Survivors were watched while they showered,[135] fondled,[136] forced to give oral sex or masturbate perpetrators,[137] digitally penetrated[138] and raped.[139] Some staff members groomed survivors with gifts, such as lollies or cigarettes, before sexually abusing them.[140]

59. Survivors told the Inquiry they were sexually abused by painting instructors,[141] the assistant principal,[142] female nurses,[143] the night watchman,[144] and other staff members.[145] This sometimes took place in the secure facilities, or at the perpetrator’s home or private quarters.

60. In one incident at Kohitere Centre in the 1980s, a boy was showering when a staff member put a plastic bag over his head and raped him.[146] Two survivors describe being anally penetrated with broom handles by staff in the secure wing of Kohitere Centre.[147] Hokio School cook Michael Ansell, who sexually abused many boys at the residence, once tied a survivor to a coffee table and anally raped him, and at other times penetrated him with different objects. The rapes were rough and caused significant pain.[148]

Survivors were sexually abused by peers

61. Survivors were sexually abused by peers, often as part of the overall bullying and violence. About one quarter of registered survivors from Hokio School and Kohitere Centre who spoke to the Inquiry mentioned sexual abuse by peers.[149] The sexual abuse took place away from staff supervision in the dormitories[150] or in secluded areas,[151] such as the sand dunes at Hokio School.[152] One survivor described getting a “sexual stomping” when he was raped after moving from the Kohitere Centre dorms to the cottages.[153]

62. Survivors at both settings recalled a sexual ‘game’ called ‘bingo’.[154] At 13 years old NZ European / Māori survivor Deane Edwards (Ngāti Porou) was forced to participate with a group of older boys:

“We played a game of ‘bingo’ and the boy who lost had to perform oral sex or masturbate other residents. I believe the staff knew about this as I heard staff members often ask if we were ‘playing bingo tonight’.”[155]

Survivors were subjected to psychological and verbal abuse

63. Survivors were subjected to psychological and verbal abuse. Survivors were put down,[156] told they were worthless,[157] and unwanted.[158] Staff would swear at them,[159] call them names,[160] and constantly threaten them with violence.[161] Survivors also described dehumanising practices such as having their clothes taken away, and being referred to as property[162] or a number,[163] rather than as a child or young person needing love and care. NZ European / Māori survivor Mr GD (Ngāi Tahu) told the Inquiry:

“[They] told me that my mother was meant to be coming up from the South Island that weekend to visit me, which got me excited ... I later found out that she was never visiting that weekend at all – it was all a lie from staff, to crush me.”[164]

64. Survivors were consistently told they were destined for prison.[165] NZ European survivor Desmond Hurring told the Inquiry:

“Staff at Kohitere constantly put me down and told me that I would end up in prison ... I was also threatened with being kept as a State ward until I turned 18. I was told I would be sent to borstal.”[166]

65. NZ European survivor Wayne Keen told the Inquiry about the impact of the verbal abuse from staff: “I was always being told that I was useless, hopeless, that I couldn’t do anything. I started to believe it after a while.”[167]

66. NZ European survivor Mr JM, who was at Kohitere Centre in the late 1970s, said that if a boy died by suicide, staff would force children and young people to view their dead bodies: “They would say ‘this is what happens to the weak’ and stuff like that.”[168]

67. Survivors also told the Inquiry they witnessed or heard other children and young people being abused[169] and described the impact that this had on them:

“It really scared us and that's why they made us watch … Seeing what happened to the other boys affected me more than what happened to me throughout my life. Being made to watch that sort of thing was a form of abuse.”[170]

Use of the ‘secure unit’ was inappropriate and led to abuse

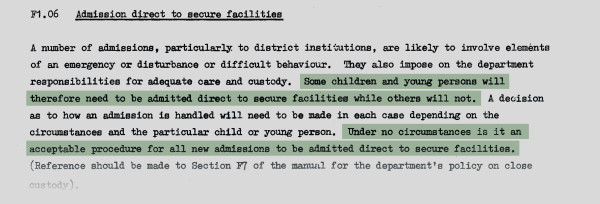

68. Many children and young people were put in solitary confinement, commonly known as ‘secure’. The 1957 Child Welfare Division Field Officer’s Manual set out an array of provisions that needed to be complied with when a State ward was placed in a secure unit, including that it should be regarded as an emergency procedure.[171] The 1975 Residential Workers Manual placed strict conditions on the use of ‘secure’, including that it should be regarded as an emergency procedure, and that it should not be used routinely on admission to the institutions[172] but only occasionally to prevent running away.[173] The Children and Young Persons (Residential Care) Regulations 1986 did not provide for punishment as grounds for admission to secure.[174] However, the secure unit was not used solely after children and young people who ran away.[175] The Inquiry found that solitary confinement was used for other reasons than were allowed.

69. The secure unit at Hokio School had two rooms, with concrete walls and steel doors. Bedding was removed during the day “so boys wouldn’t be comfortable”.[176] A Hokio School staff member said most of the physical abuse from staff happened in the secure unit.[177] One survivor described being “locked up in the secure block for months” and on each day being woken at 5am for a cold shower and personal training. During personal training, Māori survivor Mr SN would be booted and hit by staff who would later torment him by making him stand up in his cell for the rest of the day. He said: “If I was caught lying down in my cell, [they] would come flying through the door and punch me”.[178]

70. As Hokio School did not have a large secure unit, boys were often sent to the secure unit at Kohitere Centre.[179] Sometimes they were sent to Lake Alice Child and Adolescent Unit if they “had to be locked up for longer”.[180] The secure unit at Kohitere Centre also held children and young people on remand or awaiting transfer to other institutions.[181] In one case a 14-year-old boy who had murdered a 6-year-old girl was kept in isolation at the Kohitere Centre secure unit, which was “totally inadequate for long-term detention”.[182] NZ European survivor Mr BY told the Inquiry he was made to share a room with a boy convicted of violent crime and sexual assault.[183]

71. The conditions of the Kohitere Centre secure unit were completely unsuitable. The structure was modelled on the secure facility at Arohata prison[184] and described as ‘foreboding’.[185] Cells were small, with only a bucket for washing, and a mattress. Survivors said their mattress was removed during the day and the floor hosed down so they couldn’t sit.[186] Survivors said they received little to no education while in secure.[187] They were also physically abused.[188] Others told the Inquiry staff members would spit in their food.[189] Secure was colloquially referred to as ‘Disneyland’.[190] NZ European survivor Kevin England said:

“You would joke that you were going for a holiday to Disneyland. Everyone had the attitude that you hadn't been to Kohitere until you had been to Disneyland.”[191]

72. Most survivors stated they were either left alone all day or subjected to excessive physical training,[192] which was regularly coupled with violence from staff.[193] Several survivors said the staff in secure were trying to ‘break’ them.[194]

73. In the 1970s a growing number of boys were admitted to secure. In 1973, the Kohitere Centre assistant principal described the understaffed and inadequate conditions of the secure block: “If we continue under the present physical and staffing set-up, we will achieve little more than to condition boys to accept borstal later.”[195] This sentiment was echoed in the 1976 Kohitere Centre annual report, which said prison would be preferable to the secure block.[196]

74. In 1983 Social Welfare introduced specific guidelines to ensure better monitoring of secure placements.[197] All placements for more than 14 days required specific justification and notification to Social Welfare head office.[198] A November 1983 report noted that from January to October 1983, 43 boys at Kohitere Centre were in secure for more than 14 days, with only nine of these placements complying with the guidelines.[199] In 1987, 58 admissions to secure at Hokio School and Kohitere Centre were incorrectly documented, with the reason for placement not in compliance with regulations.[200] The Inquiry did not receive any evidence to show what the Department’s response was, if any, to these breaches.

75. NZ European survivor Mr BY told the Inquiry he spent 18 days in secure when he first arrived at Kohitere Centre.[201] Māori survivor Daniel Rei (Ngāti Toa Rangatira) was kept in secure for a total of more than 154 days during his placement in the 1980s, earning him the nickname the “block king”.[202] Māori survivor Mr SK (Ngāti Porou) spent 320 days in secure over a 563-day period from the time he was 13 years old.[203] After his release from Kohitere Centre, Mr SK told the Inquiry he spent most of his life in prison and admitted to being “extremely violent”.[204] In an expert report provided to the Inquiry, adolescent forensic psychologist Dr Enys Delmage discussed the risks of solitary confinement on the adolescent brain, including the breaking of social connections and a distrust of authority.[205]

Survivors were subjected to racism and cultural neglect

76. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori were the majority of the population at both Hokio School and Kohitere Centre from the mid-1960s onwards. Although there were Māori staff at both institutions, survivors described an environment that did not encourage te reo Māori.[206] Māori survivor Hohepa Taiaroa (Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Kahungunu) told the Inquiry:

“I couldn't be Māori. I couldn't be me. I had to act like a Pākehā. To me that's racism. That's abuse. If we spoke te reo, the staff would give us mean looks or give us all the shit jobs. It was subtle pacification.”[207]

77. Deaf NZ European / Māori survivor Mr JV described a similar experience:

“I speak te reo and was raised speaking te reo. But it was like an offence to learn Māori culture in those places. Nobody spoke it, I tried to speak to a couple of staff about it but they would just tell me to shut up.”[208]

78. One Māori survivor said there was little provision of any meaningful cultural education.[209] Māori survivor Paora (Paul) Sweeney (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Hako) said: “I just knew a Pākehā system that was thrashing me.”[210] Samoan survivor Fa’amoana Luafutu, who was at Kohitere Centre in the 1960s, told the Inquiry: “The place had no function to meet the needs of a Samoan like me.”[211]

79. Some survivors from Kohitere Centre described positive experiences,[212] such as participating in the kapa haka group.[213] Māori survivor Mr GV (Ngāpuhi) remembered a visiting kaumatua:

“Mr Poutama would take all the Māori boys out of Kohitere on the weekends to teach us how to catch eels, how to set the nets for fishing and other things … I can see now that he was teaching me about my culture and about tikanga.”[214]

80. Survivors also experienced racist verbal abuse.[215] One Māori survivor remembers being called a “useless black bastard”.[216] A Māori survivor said one Hokio School staff member repeatedly called him a “little black c**t” who would “never amount to much”.[217]

81. Samoan survivor David Williams (aka John Williams) said that the sexual abuse he suffered at Hokio School was coupled with racial abuse: “‘Coconut’ or ‘bunga’ or ‘fresh off the boat’ was how Pacific Islanders were referred to in those years.”[218] Niuean / Māori survivor Mr VV (Ngāpuhi) told the Inquiry that the principal wrote: “I hadn't been very productive as a member of the work group, and suggested that I could return to the Islands, ‘where his present way of life could be acceptable’.”[219]

82. Because tamariki and rangatahi Māori were the majority at both institutions from the mid-1960s, they were therefore more likely to be subjected to abuse. The enduring impact of this abuse is summed up by Cook Islands / Māori survivor Tani Tekoronga (Ngāi Tahu) reflecting on the Māori cultural group at Hokio School:

“A large number of boys that I was in the culture group with are either dead or in prison now ... some I believe by suicide … [Another boy] died after jumping off a bridge and drowning in a river while trying to escape police, after running away from Hokio … Every one of the boys in that photo has suffered.”[220]

Survivors’ wellbeing and mental health was neglected

83. In 1971, the Hokio School Principal said of the growing number of children and young people coming from psychiatric settings: “In terms of the specialist services these children need we fell short.”[221] In annual reports he consistently stated that the fortnightly visits from psychological services were not enough and requested Hokio School and Kohitere Centre be provided with an in-house psychologist.[222] A psychologist was available to Hokio School by the early 1980s, however an inspection report revealed that the psychologist was not positively viewed by the staff.[223]

84. Those with psychological needs were not just confined to those coming from psychiatric settings. Many of the children and young people were neurodiverse and suffered the impacts of trauma.[224] However, these institutions consistently failed to provide proper care for the children and young people they were entrusted with. NZ European survivor Philip Laws said the abuse and lack of support for his dyslexia has “ruined my life”.[225]

85. A 1969 report into staff rostering at Kohitere Centre found that housemasters, who were considered a boy’s ‘father figure’, only spent around 8.4 percent of their time counselling the boys.[226] In 1987, Kohitere Centre’s assistant principal wrote to the principal outlining the need for specialist psychiatric services that had been affected by funding cuts. The principal disagreed.[227]

86. Two survivors told the Inquiry they were sent to Hokio School or Kohitere Centre after attempting suicide at another boys’ home.[228] However, they did not receive any sort of support or counselling. Māori survivor Paora (Paul) Sweeney (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Hako), who became an orphan at 11 years old, described the state he was in when he was transferred to Kohitere Centre in the 1970s: “I should have had grief and loss counselling for the loss of my parents and my sisters, but I wasn’t given anything. I was beaten instead.”[229]

87. NZ European survivor Tony Lewis said although he received counselling once a week at Kohitere Centre, because of the strong no-narking culture he didn’t disclose his abuse. He said there were too many children and young people for counsellors to provide adequate support.[230] Kohitere Centre NZ European survivor Mr A said how, despite his records saying he needed counselling for his behaviour and his use of solvents, he never received it.[231] He was also denied psychological treatment as he was supposedly “too sophisticated” to benefit.[232]

88. The sniffing of solvents was fairly common at Kohitere Centre[233] but not much was done to address this, other than to punish those doing it. A registered nurse at Kohitere Centre in the 1980s described one incident of a boy in a semi-conscious state after sniffing petrol: “I said, ‘get an ambulance’. And they [other staff] didn’t want to, they said, ‘he’s just sleeping’ … so they did very reluctantly.”[234]

Survivors experienced educational neglect

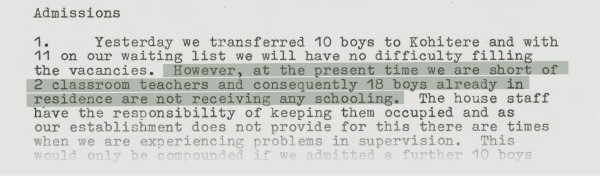

89. Some survivors told the Inquiry they received little formal schooling while in care, particularly at Kohitere Centre, where the focus tended to be on trades and workplace training. Legally, all children and young people were required to attend school up to the age of 16, however, much of the education provided appeared to be remedial.[235] The school employed qualified teachers and there was the option to complete School Certificate through the Correspondence School.[236] But the quality and extent of this education was variable and impacted by staffing issues. The school was often staffed by a single teacher, or by those ill-equipped to provide necessary remedial support.[237]In the 1970s a new system was introduced at Kohitere Centre, with boys expected to complete at least three months of school before moving on to work training.[238]

90. In 1968, a letter from the head teacher at Hokio School identified multiple issues with the school environment, in particular the inability to provide boys with the remedial one-to-one teaching they needed. A request for further teaching staff was made, noting “unless the educational needs of these boys can be adequately met in this school, educational failure will continue to plague them and this in turn could easily contribute to further breakdowns in their social behaviour”.[239] Nearly a decade later, the same issues persisted.[240] In her brief of evidence to the Inquiry, Ministry of Education Chief Executive Iona Holsted acknowledged that staffing issues impacted the education provided at the residences. [241]

91. The Social Work Manual in 1970 and 1984 both stated that “as far as possible State wards should be regarded in the same way as other children and should be encouraged to continue their formal schooling for as long as they are drawing benefit from it”. [242]

92. Niuean / Māori survivor Mr VV (Ngāpuhi), who was at Hokio School in the 1970s, told the Inquiry that he was “so focused on self-preservation” that he didn’t learn anything.[243] Two survivors told the Inquiry they left Kohitere Centre barely able to read or write.[244] Māori survivor Mr JI (Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Raukawa) told the Inquiry: “I did not learn anything because there was not much teaching and a lot of just sitting around.”[245]

93. NZ European / Māori survivor Peter Brooker (Waitaha) said he aspired to complete School Certificate at Kohitere Centre in 1984. He achieved the “highest score they had ever had on their school entry tests” but was told he couldn’t go to school: “Instead, I learnt how to prune trees.”[246]

Work training was sometimes abusive

94. The main educational aspect at Kohitere Centre focused on trades training, in areas such as farming, carpentry and forestry. Towards the end of their placement, some boys also held jobs in the community to help prepare them for their transition out of care. Two survivors described the work as slave labour.[247] Michael Rush, who worked at the freezing works in Levin, said he loved the job but felt as though his wages were being “ripped off”.[248] Boys with jobs in the community were made to pay board.

95. Some survivors described the workplace training they received as one positive aspect of their overall care experience.[249] One survivor received his tractor licence[250]; another, his welding certificate.[251] Despite this, survivors were often made to work in unsafe conditions that led to injuries. One survivor even lost his finger in the woodworking workshop.[252] Most injuries happened to boys in the forestry unit.

The forestry programme at the Kohitere Centre led to physical abuse in many cases

96. Forestry work was physically demanding and involved planting, pruning, wood splitting and other labour. Instructors were typically younger men with forestry industry experience. Few received any additional training to be instructors or work with young people.[253] Certain instructors believed that firm discipline was necessary, and that residential staff didn’t understand their situation.

97. Some forestry staff physically ‘disciplined’ children and young people, including kicking them ‘in the backside’ and pushing them down a hill.[254] Former instructor Sonny Cooper told the Inquiry that instructors were left to discipline children and young people, and they all used their own methods.[255] A former Kohitere Centre assistant principal acknowledged that forestry instructors could “[take] the law into [their] own hands”.[256] There were numerous allegations of abuse against staff.[257]

98. Survivors did not receive any health and safety training[258] and often suffered injuries. Boys were hurt by falling logs, cut themselves with their axes, or broke bones. One survivor ended up in hospital with a ruptured hernia from lifting the heavy logs. When he pointed out the lump before it burst, he was told to “harden up”.[259]

99. Not all survivors had a negative experience working in the forestry unit.[260] Samoan survivor Fa’amoana Luafutu explained: “It was hard-as work. But us boys liked being away from the home, and they gave us time to be up there running around and yahooing.”[261]

Survivors used different strategies to avoid abuse

100. Survivors used different strategies to avoid abuse and ill-treatment at Hokio School and Kohitere Centre. For some, this meant ‘toeing the line’ and trying to get out as soon as possible.[262] Others told the Inquiry they would try to isolate themselves from other children and young people, including by getting sent to secure.[263]

101. One common way survivors tried to exercise agency was through running away .[264] However, once they were found, they were returned to the institutions and punished, with physical abuse,[265] humiliation,[266] harsh physical training[267] or being put into secure.[268] Staff did not try to find out the underlying reason behind the running away.

102. Māori survivor Mr GQ (Te Aupōuri) told the Inquiry that, after he was sexually abused by a staff member, he:

“started running away from Kohitere as well because I just couldn't handle it. I was a good-looking kid but I didn’t expect grown men to be coming onto me like that.”[269]

103. Running away could also end in tragedy. In one incident, two children died in a car accident after they fled.[270]

The extent of abuse and neglect

104. Abuse at Hokio School and Kohitere Centre was systemic. According to the Inquiry’s analysis of historic claims data provided by the Ministry of Social Development:

a. Of any Department of Social Welfare institution, Kohitere Centre has the highest number of allegations of abuse made by survivors (227 complainants, 812 allegations). Hokio School has the fourth highest (121 complainants, 551 allegations).[271]

b. Of the total allegations, the most common is of physical abuse (339 for Hokio School and 550 for Kohitere Centre), followed by sexual abuse (124 for Hokio School and 135 for Kohitere Centre), and emotional abuse (78 for Hokio School and 102 for Kohitere Centre).[272] There were at least four prolific sexual abusers at Hokio School.

c. Of the six staff members from across the different children’s institutions that have had more than 30 separate allegations of abuse made against them individually, and four came from Hokio School or Kohitere Centre. One Hokio School staff member had 65 allegations of abuse made against them.[273]

Footnotes

[67] Private session transcript of a survivor who wishes to remain anonymous (25 August 2020, page 29).

[68] Private session transcript of Mr UQ (24 February 2022, page 28).

[69] Witness statement of Poihipi McIntyre (14 March 2023, para 4.10.3).

[70] Private session transcript of Louis Coster (21 June 2022, page 26).

[71] Witness statement of Mr IA (2 June 2022, para 3.8).

[72] Witness statement of Roger Kahui (6 March 2023, para 3.8).

[73] Witness statement of Andrew Brown (13 July 2022, para 5.11).

[74] Witness statement of Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021), para 112).

[75] Witness statement of Mark Goold (8 June 2021, para 86).

[76] Witness statement of Darren Knox (13 May 2021, para 60).

[77] List of allegations to MSD-data analysis, datapoint (12 June 2023).

[78] One hundred and thirty-five witness statements / transcribed private sessions were analysed. One hundred and sixty-five survivors from these settings spoke to the Inquiry but some private sessions were not transcribed and could not be analysed.

[79] List of allegations to MSD-data analysis.

[80] Witness statements of Mr LT (7 March 2022, para 35); Wayne Keen (28 April 2021, para 48); Mr BY (23 July 2021, para 39) and Brian Moody (4 February 2021, para 68).

[81] Witness statements of Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 196); David Williams (aka John Williams), (15 March 2021, para 89) and Earl White (15 July 2020, para 38).

[82] Witness statements of Peter Porter (4 May 2023, para 118) and Mr A (19 August 2020, para 45).

[83] Witness statement of Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 128).

[84] Witness statement of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 103).

[85] Witness statement of Danny Akula (13 October 2021, para 99).

[86] Witness statement of Mr SB (16 March 2021, para 44).

[87] Private session transcript of Rihari. G (31 March 2022, pages 23–24).

[88] Private session transcript of survivor who wishes to remain anonymous (6 September 2022, page 13).

[89] Private session transcript of Mr UO (12 May 2021, pages 13–14).

[90] Witness statement of Mr A (19 August 2020, para 46).

[91] Witness statement of Mr JM (11 July 2022, para 32).

[92] Witness statements of Mr BE (8 May 2023, para 56) and Mr A (19 August 2020, para 44).

[93] Private session transcript of Mr GA (2 October 2019, page 4); Witness statement of Mr JV (4 May 2023, para 24).

[94] Witness statement of Mr GD (8 July 2022, para 53).

[95] Witness statement of Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 93).

[96] Witness statement of Mr VV (17 February 2021, para 33).

[97] Witness statement of Steven Long (15 October 2021, paras 92–93).

[98] Witness statement of Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 100).

[99] Witness statement of Tyrone Marks (22 February 2021, para 81).

[100] Witness statement of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 103).

[101] Witness statement of Wiremu Waikari (27 July 2021, para 248).

[102] Collated information / summary from interviews with former Hokio staff members (29 April 2012, page 8).

[103] Collated information / summary from interviews with former Hokio staff members (29 April 2012, page 8).

[104] Witness statements of Steven Long (15 October 2021, para 96); Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 161); Mr A (19 August 2020, para 84); Wayne Keen (28 April 2021, paras 64–65); Mr PF (15 December 2020, para 115) and Tyrone Marks (22 February 2021, para 124).

[105] Brief of evidence of [survivor] for the White trial (24 January 2007, para 43).

[106] Witness statement of Mr GZ (22 June 2021, para 46).

[107] Parker, W, Social welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume II: National institutions (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 73).

[108] Statement of claim in the High Court of [survivor] (4 August 2006, pages 12–13).

[109] Witness statement of Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, para 59).

[110] Witness statements of Wayne Keen (28 April 2021, para 65); Mr RX (27 March 2023, para 4.6.7); Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 78); Mr PF (15 December 2020, paras 130–131) and Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 212).

[111] Witness statement of Mr UD (10 March 2021, para 53).

[112] Collated notes / summary from interview with former Hokio and Kohitere principal (7 December 2012, page 2).

[113] Witness statements of Mr A (19 August 2020, paras 39, 75); Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, para 42); Tyrone Marks (22 February 2021, paras 85, 128); Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 101); Hohepa Taiaroa (31 January 2022, paras 26–27); of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 97); Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 252); Harry Tutahi (18 August 2021, para 76) and Toni Jarvis (12 December 2021, para 66).

[114] Based on 135 witness statements and transcribed private sessions that were analysed. In total 165 survivors from these settings spoke to the Inquiry. As untranscribed private sessions were not included in the analysis the numbers may be higher.

[115] Witness statement of Mr A (19 August 2020, para 75).

[116] Witness statement of Tony Lewis (21 August 2021, para 37).

[117] Witness statement of Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, paras 101–102).

[118] Witness statement of Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 189).

[119] Background interview with former residential social worker (13 February 2006, page 2).

[120] Interview with former senior counsellor (20 November 2007, page 6); Daniel Rei v Ministry of Social Development: transcript of interview with former staff member (20 January 2010, page 6); Daniel Rei v Chief Executive: transcript of interview with former staff member (11 November 2009, page 1); Department of Social Welfare, 3-month review of a young person in care (22 November 1983, page 5).

[121] Witness statement of Tyrone Marks (22 February 2021, para 89).

[122] Witness statements of Mr JL (3 November 2022, para 4.3.3) and Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, para 51).

[123] Witness statement of Tony Lewis (21 August 2021, para 39).

[124] Witness statement of Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 117).

[125] Witness statement of Danny Akula (13 October 2021, paras 90, 96); Brief of evidence of [survivor] (28 January 2007, para 41).

[126] A violent and sudden punch intended to knock someone out.

[127] Witness statement of Mr FI (30 July 2021, paras 38-39).

[128] Witness statements of Poihipi McIntyre (14 March 2023, para 4.10.6); Michael Rush (16 July 2021, paras 93–96); Deane Edwards (27 March 2023, para 4.13.5) and Mr HD (27 July 2021, paras 105–106).

[129] Cooper, S, Culture of abuse and perpetrators of abuse at Department of Social Welfare institutions: A paper based on the civil legal proceedings of clients represented by Sonia M Cooper (n.d., page 22); Witness statement of Poihipi McIntyre (14 March 2023, para 4.10.6).

[130] Collated notes / summary from interview with former Hokio and Kohitere principal (7 December 2012, page 2).

[131] Witness statements of Steven Long (15 October 2021, para 97); Brian Moody (4 February 2021, para 61); Mr JI (April 2023, para 4.2); Mr VV (17 February 2021, para 24) and Mr GV (27 July 2021, para 55).

[132] Witness statement of Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 200).

[133] List of allegations to MSD-data analysis, datapoint 12 (June 2023).

[134] Based on 135 witness statements and transcribed private sessions that were analysed. In total 165 survivors from these settings spoke to the Inquiry. As untranscribed private sessions were not included in the analysis the numbers may be higher.

[135] Witness statement of Mr FI (30 July 2021, para 48).

[136] Witness statement of Mr PF (15 December 2020, para 140).

[137] Witness statements of Earl White (15 July 2020, para 41) and Mr GQ (11 February 2021, para 101).

[138] Witness statements of Mr UD (10 March 2021, para 47) and Mr FI (30 July 2021, para 46).

[139] Witness statements of David Williams (aka John Williams), (15 March 2021, para 104); Mr UD (10 March 2021, para 48) and Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 105).

[140] Witness statements of Mr GQ (11 February 2021, para 101); Mr UD (10 March 2021, para 50); Earl White (15 July 2020, para 41) and Hone Tipene (22 September 2021, para 184).

[141] Witness statement of Mr UD (10 March 2021, paras 93–94).

[142] Statement of [survivor] for ‘Operation Lake Alice’ (13 June 2001, paras 33–34).

[143] Witness statement of Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 226–231).

[144] Witness statements of Mr PF (15 December 2020, para 149) and Hone Tipene (22 September 2021, para 178); Cooper Legal, Settlement offer of [survivor] (18 August 2020, para 54).

[145] Witness statement of Mr SJ (23 February 2023, para 108).

[146] Private session transcript of MR VI (25 August 2020, pages 31–32).

[147] Private session transcript of Mr UL (23 November 2022, pages 14–16); Witness statement of Mr JV (4 May 2023, para 24).

[148] Witness statement of Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 105–106).

[149] Based on 135 witness statements and transcribed private sessions that were analysed. In total 165 survivors from these settings spoke to the Inquiry. As untranscribed private sessions were not included in the analysis the numbers may be higher.

[150] Witness statements of Brent Mitchell (15 April 2021, paras 112–113) and Philip Laws (23 September 2021, para 3.66).

[151] Witness statements of Philip Laws (23 September 2021, para 3.73) and Toni Jarvis (12 December 2021, para 68).

[152] Witness statement of Mr FI (30 July 2021, para 34).

[153] Witness statement of Mr HD (27 July 2021, para 132).

[154] Witness statement of Peter Brooker (6 December 2021, para 177).

[155] Witness statement of Deane Edwards (27 March 2023, para 4.13.8).

[156] Witness statements of Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, para 57); Tony Lewis (21 August 2021, para 43) and Deane Edwards (27 March 2023, para 4.13.9).

[157] Witness statements of Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 80); Peter Brooker (6 December 2021, para 156); Mr JL (3 November 2022, para 4.3.4) and Mr JP (1 April 2022, para 65).

[158] Witness statement of Mr SK (10 February 2021, para 336).

[159] Witness statements of Earl White (15 July 2020, para 39) and Hone Tipene (22 September 2021, para 196).

[160] Witness statements of Peter Brooker (6 December 2021, para 156) and Hurae Wairau (29 March 2022, para 67).

[161] Witness statement of Earl White (15 July 2020, para 39).

[162] Witness statement of Brian Moody (4 February 2021, para 79).

[163] Witness statements of Hohepa Taiaroa (31 January 2022, para 62) and Toni Jarvis (12 December 2021, para 65).

[164] Witness Statement of Mr GD (8 July 2022, para 71).

[165] Witness statements of Mark Goold (8 June 2021, para 68) and Mr BE (8 May 2023, para 61).

[166] Witness statement of Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, paras 57–58).

[167] Witness statement of Wayne Keen (28 April 2021, para 51).

[168] Witness statement of Mr JM (11 July 2022, para 36).

[169] Witness statements of Tani Tekoronga (19 January 2022, para 62) and Poihipi McIntyre (14 March 2023, para 4.10.10).

[170] Witness statement of Mr SB (16 March 2021, paras 55, 57).

[171] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division, Field Officer’s Manual (1957), J.124(xiv).

[172] Department of Social Welfare, Residential Workers Manual (1975), F1.06 (page 118) and F7.02 (page 144).

[173] Ministry of Social Development, National policies and practices outline (1 April 2006, page 14).

[174] Children and Young Persons (Residential Care) Regulations 1986 (October 1986, reg 28 page 5); Ministry of Social Development, National policies and practices outline (1 April 2006, page 20).

[175] Collated information / summary from interviews with former Hokio School staff members (29 April 2012, pages 2, 4).

[176] Collated information / summary from interviews with former Hokio School staff members (29 April 2012, page 5).

[177] Collated information / summary from interviews with former Hokio School staff members (29 April 2012, pages 4–5).

[178] Witness statement of Mr SN (30 April 2021, paras 116–120).

[179] Witness statement of David Williams (aka John Williams), (15 March 2021, para 132).

[180] Collated notes / summary from interview with former Hokio and Kohitere principal (7 December 2012, page 2).

[181] Witness statements of Mr IA (2 June 2022, para 3.4) and Mr KQ (6 January 2023, page 6).

[182] Letter from senior education officer, Educational programmes for the secure unit at Kohitere (5 December 1977).

[183] Witness statement of Mr BY (23 July 2021, para 24).

[184] Daniel Rei v Chief Executive: transcript of interview with former staff member (11 November 2009, page 5).

[185] Campbell, JB, The long term residential treatment of delinquent boys by the Child Welfare Division of the Department of Education, Master’s Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington (1971, page 8).

[186] Witness statements of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 113); Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 248) and Mr JM (11 July 2022, paras 30–31).

[187] Witness statements of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 115); Tyrone Marks (22 February 2021, para 135) and Mr GZ (22 June 2021, para 35).

[188] Witness statements of Tyrone Marks (22 February 2021, para 123); Mr AA (14 February 2021, para 57) and Mr SB (16 March 2021, para 44).

[189] Witness statement of Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 87); Private session of Dave Charlson (24 November 2021, page 30).

[190] Witness statements of Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, para 54) and Peter Brooker (6 December 2021, para 136).

[191] Witness statement of Kevin England (28 January 2021, para 138).

[192] Witness statements of Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 248); Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 106); Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, para 53); Mr GZ (22 June 2021, para 44) and Mr JP (1 April 2022, para 64)).

[193] Witness statements of Mr A (19 August 2020, para 54); Darren Knox (13 May 2021, para 64) and Mr RX (27 March 2023, para 4.6.6).

[194] Witness statements of Desmond Hurring (17 February 2021, para 53); Mr GZ (22 June 2021, para 45) and of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 111).

[195] Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Annual Report 1973 (page 92).

[196] Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Annual Report 1976 (page 79).

[197] Visit to Kohitere on 14–18 November 1983 (page 5). These were later formalised in the 1984 Social Work Manual and the 1986 Regulations.

[198] Visit to Kohitere on 14–18 November 1983 (page 5).

[199] Visit to Kohitere on 14–18 November 1983 (page 6).

[200] Letter from Assistant Director-General to Director-General, re: admission to secure care (30 August 1988, page 3).

[201] Witness statement of Mr BY (23 July 2021, para 23).

[202] Witness statement of Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 158).

[203] Witness statement of Mr SK (10 February 2021, para 375).

[204] Witness statement of Mr SK (10 February 2021, para 415).

[205] Expert witness report of Dr Enys Delmage (13 June 2022, page 28).

[206] Witness statements of Mr LT (7 March 2022, para 42) and Mr JK (30 September 2022, para 19); Private session transcript of Mr VH (22 February 2022, page 68).

[207] Witness statement of Hohepa Taiaroa (31 January 2022, para 38).

[208] Witness statement of Mr JV (4 May 2023, para 33).

[209] Witness statement of Deane Edwards (27 March 2023, para 5.1).

[210] Witness statement of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 202).

[211] Witness statement of Fa’amoana Luafutu (5 July 2021, para 57).

[212] Witness statement of Daniel Stretch (2 August 2021, para 47); Private session transcript of Rihari. G (31 March 2022, page 29).

[213] Witness statement of Jovander Terry (29 June 2021, para 149).

[214] Witness statement of Mr GV (27 July 2021, paras 102-104).

[215] Witness statement of Jovander Terry (29 June 2021, para 147).

[216] Witness statement of Michael Taylor (24 April 2023, para 2.14).

[217] Brief of evidence of [survivor] for the White trial (24 January 2007, para 44).

[218] Witness statement of David Williams (aka John Williams), (15 March 2021, para 112).

[219] Witness statement of Mr VV (17 February 2021, para 55).

[220] Witness statement of Tani Tekoronga (19 January 2022, paras 75–76).

[221] Hokio Beach School, Annual Report 1971 (page 123).

[222] Hokio Beach School, Annual Report 1968 (page 199); Hokio Beach School, Annual Report 1969 (page 178); Hokio Beach School, Annual Report 1970 (page 138); Hokio Beach School, Annual Report 1971 (page 127); Hokio Beach School, Annual Report 1972 (page 101); Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Annual Report 1973 (page 89).

[223] Inspection visit to Hokio Beach School 1981 (page 8).

[224] Witness statements of Philip Laws (23 September 2021, para 2.6) and Mr A (19 August 2020, para 96).

[225] Witness statement of Philip Laws (23 September 2021, paras 4.1, 4.8, 4.10).

[226] State Services Commission, Child Welfare Division: Kohitere (September 1970, page 5).

[227] Letter from PT Woulfe to regional director re: request for specialist services (14 July 1987).

[228] Witness statements of Sharyn (16 March 2021, para 153) and Philip Laws (23 September 2021, paras 3.54–3.55).

[229] Witness statement of Paora (Paul) Sweeney (30 November 2020, para 89).

[230] Witness statement of Tony Lewis (21 August 2021, para 51).

[231] Witness statement of Mr A (19 August 2020, para 79).

[232] 3 monthly report of Mr A (28 July 1987, pages 37–38).

[233] Witness statements of Mr GQ (11 February 2021, para 98); Mr A (19 August 2020, para 52); Darren Knox (13 May 2021, para 78) and Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 208).

[234] Daniel Rei v Ministry of Social Development: transcript of interview with former staff member (20 January 2010, page 9).

[235] Brief of evidence of Secretary for Education and Chief Executive Iona Holsted for the Ministry of Education at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 8 August 2022, page 62).

[236] Ministry of Social Development, Understanding Kohitere (2009, page 31); Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume II: National institutions (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 64).

[237] Parker, W, Social welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume II: National institutions (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 64).

[238] Ministry of Social Development, Understanding Kohitere ( 2009, pages 89, 227).

[239] Letter from Hokio School head teacher to the principal, school staffing (11 November 1968, page 2).

[240] Letter from Hokio School principal to Director-General Social Welfare (9 September 1976, page 1).

[241] Brief of evidence of Secretary for Education and Chief Executive Iona Holsted for the Ministry of Education at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 8 August 2022, page 62).

[242] Department of Social Welfare, Social Workers’ Manual 1970 (section J14, page 249); Department of Social Welfare, Social Work Manual 1984 (section N5.1, page 88).

[243] Witness statement of Mr VV (17 February 2021, para 35).

[244] Witness statements of Mr SK (10 February 2021, para 369) and Tony Lewis (21 August 2021, para 46).

[245] Witness Statement of Mr JI (April 2023, para 4.2)

[246] Witness statement of Peter Brooker (6 December 2021, paras 181–184).

[247] Witness statements of Mr BY (23 July 2021, para 43) and Tony Lewis (21 August 2021, para 47).

[248] Witness statement of Michael Rush (16 July 2021, para 105).

[249] Witness statements of Walter Warner (28 June 2021, paras 113–114) and Tony Lewis (21 August 2021, para 50); Private session transcript of Mr VG (3 November 2021, page 37).

[250] Witness statement of Greg from Owairaka (10 March 2021, para 103).

[251] Witness statement of Darren Knox (13 May 2021, para 74).

[252] Witness statement of Bryon Nichol (24 March 2021, para 36).

[253] Witness statement of staff member (1 March 2010, para 8); Forestry instructor notes he received training from forestry instructors and notes being provided social worker training but this was not taken up by other instructors. Ministry of Social Development v Daniel Rei: Interview (22 February 2010, page 3).

[254] Witness statements of Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 139) and Craig Dick (26 March 2023, para 5.11.9); Private session transcripts of Mr UT (1 October 2019, page 16) and survivor who wishes to remain anonymous (13 August 2020, page 5).

[255] Witness statement of Sonny Cooper (1 March 2010, para 34).

[256] Daniel Rei vs Chief Executive: Interview with former assistant principal (11 November 2009, page 9).

[257] Witness statements of Daniel Rei (10 February 2021, para 139) and Craig Dick (26 March 2023, para 5.11.9); Private session transcripts of Mr UT (1 October 2019, page 16) and survivor who wishes to remain anonymous (13 August 2020, page 5).

[258] Witness statement of Kevin England (28 January 2021, para 160).

[259] Private session transcript of survivor who wishes to remain anonymous (13 August 2020, page 5).

[260] Witness statements of Wiremu Waikari (27July 2021, para 264); Hohepa Taiaroa (31 January 2022, para 57); Mr HS (27 March 2022, paras 4.4.5–4.4.6) and Kevin England (28 January 2021, para 156).

[261] Witness statement of Fa’amoana Luafutu (5 July 2021, para 53).

[262] Witness statements of Philip Laws (23 September 2021, para 3.62); Sharyn (16 March 2021, para 158) and Hurae Wairau (29 March 2022, para 60). Interview with former senior counsellor (20 November 2007, page 9).

[263] Witness statements of Mr SK (10 February 2021, para 301) and Hohepa Taiaroa (31 January 2022, para 43); Private session transcript of a Mr UT (1 October 2019, page 20).

[264] Witness statements of Mr SK (10 February 2021, para 351); Mr UD (10 March 2021, para 59); Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 125); Mr AA (14 February 2021, para 60); Mr GZ (22 June 2021, paras 43-44); William MacDonald (4 February 2021, para 163); Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.10) and Mr SB (16 March 2021, para 48).

[265] Witness statements of Toni Jarvis (12 December 2021, para 81) and Mr CE (8 July 2021, para 48).

[266] Witness statement of Mr GZ (22 June 2021, para 44).

[267] Witness statement of Wayne Keen (28 April 2021, para 65).

[268] Witness statements of Mr GD (8 July 2022, paras 58–59); Lindsay Eddy (24 March 2021, para 127); Mr UD (10 March 2021, para 103); Peter Brooker (6 December 2021, para 131); Mr A (19 August 2020, para 52) and Darren Knox (13 May 2021, para 62).

[269] Witness statement of Mr GQ (11 February 2021, para 104).

[270] Witness statement of Tani Tekoronga (19 January 2022, para 67); Memo director general: Abscondings and deaths in car accidents (11 May 1973); Interview with Robin Wilson (7 July 2022, page 16).

[271] List of allegations to MSD-data analysis, datapoint 12, (June 2023). This information represents total allegations and complainants but it doesn’t take into account residence sizes. Of the four institutions with the most allegations (Kohitere, Epuni Boys’ Home, Hokio, Ōwairaka Boys’ Home), Kohitere had more residents (up to 120) than the other three (from 40 to 60). Kohitere and Hokio were both long-stay institutions while Ōwairaka and Epuni were short-stay homes.

[272] There also claims for neglect, ‘other’, or ‘not applicable’. List of allegations to MSD-data analysis, datapoint 12, (June 2023).

[273] Summary of abuse claims made to Ministry of Social Development.