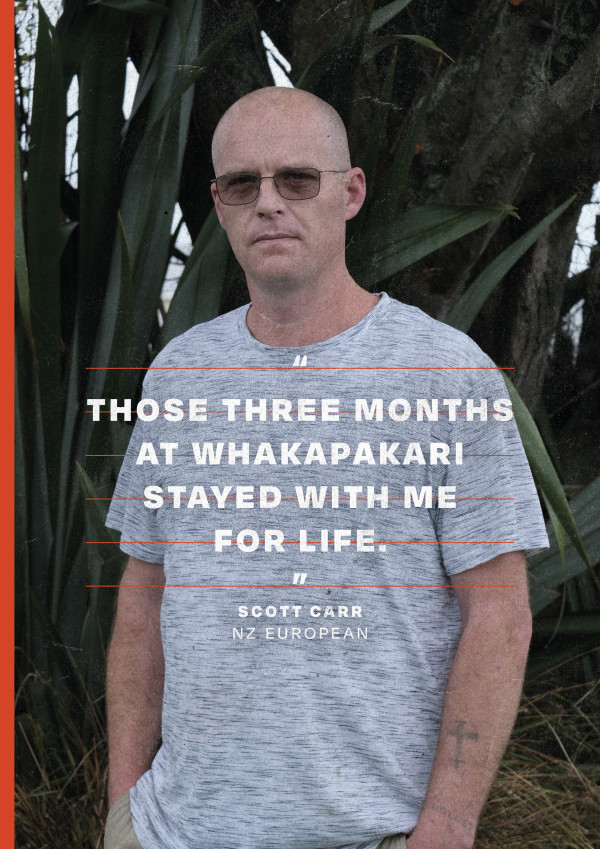

Survivor experience: Scott Carr Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Scott Carr

Year of birth 1983

Type of care facility Foster homes; Boys’ home – Epuni Boys’ Home in Te Awa Karangi ki Tai Lower Hutt; Te Whakapakari Youth Programme on Aotea Great Barrier Island.

Ethnicity NZ European

Whānau background Scott has two older brothers and one older sister. During his childhood, his parents worked a lot.

Current Scott has ongoing health issues and had a heart attack when he was 40. Scott believes that his experiences in care and the resulting PTSD contributed to his heart attack. He struggled with alcohol addiction and has been sober for over five years.

My parents believed good parenting meant working hard, all the time. I ended up in care after someone contacted CYFS to let them know that “something was not right” at home. I wasn’t physically abused, but I was not a priority. My dad never spoke to us.

I got suspended from school when I was 13 years old. I was bored and lonely, which is when I started drinking and hanging out with an older crowd. I had also tried to commit suicide in the past, but I wasn’t offered any help, despite me telling CYFS I was suicidal. I also ran away from home and appeared in court several times.

I was sent to Epuni and later to Whakapakari, aged 14.

When I arrived at Whakapakari, I was strip-searched to ensure I wasn’t concealing anything. I was then placed in a tent group, who were assigned to chopping and carting firewood. We did this from early in the morning to late at night.

I asked my tent supervisor a question one day and he told me to keep my ‘ballhead’ comments to myself. I said I didn’t like being called a ballhead, and he beat me and threatened to kill me. He knocked me unconscious and left me lying there covered in blood. The other boys were ordered not to help me or check on me. I still have multiple scars across the back of my head. I was so distressed I seriously considered throwing myself off a cliff to get away from Whakapakari.

I took to sleeping with a fish filleting knife that I stole from the kitchen in case he attacked me again. He was a bully. He’d deflate the tyre of the wheelbarrow and when I couldn’t push it properly, he’d throw firewood at me.

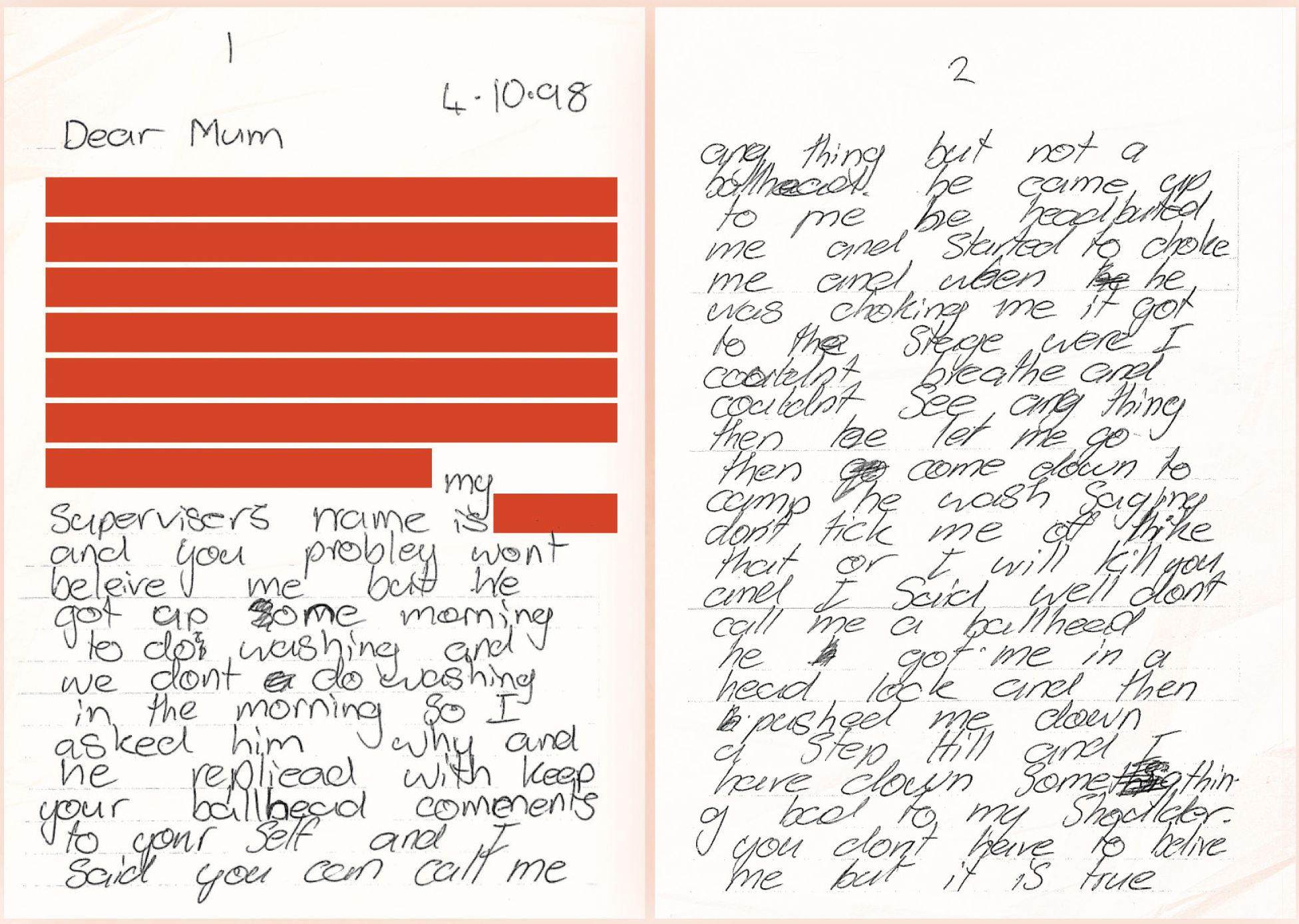

After I had been there for a few weeks, the camp supervisor found a letter I had written to my mother complaining about the violence the tent supervisor had inflicted on me. I was told to apologise to the tent supervisor repeatedly, until I cried. To stop me crying, he choked me until I couldn’t breathe. The camp supervisor wrote down my mother’s address and told me he would go there, and make her pay if I ever wrote negative things about Whakapakari again and ‘get’ me or my family if I ever told anyone about the choking. I then had to rip up the letter and put it in the fire.

I was also assaulted, bullied and harassed by other residents while staff watched. I was exposed to serious violence – I would describe this as ‘cage fighting’, where staff organised residents to fight, for their own entertainment. While I didn’t always participate, I had to watch.

If I misbehaved, I was forced to do things like carry sacks of stones up a hill as punishment. Despite my parents sending me a new pair of gumboots, I was made to carry these sacks in bare feet, because the supervisor gave my gumboots to another resident. The path up the hill was very rocky, and my feet got covered in cuts that became infected.

Another supervisor made me dig holes in the ancestral graveyard to bury skull and skeleton bones, and told me if I didn’t behave, I’d end up there too. He also told all the residents to call me ‘white bread’ because I was Pākehā.

I wasn’t looked after properly at Whakapakari. We were sent to another island, known as Alcatraz, where I was very cold and not given any food. I was told to find oysters for food. I was often hungry because we were responsible for catching our own fish to eat, and if we didn’t, we only had potatoes and porridge. My mother would send me food parcels, but the staff always took most of the food out, either to eat it themselves or give to other residents.

I was only allowed to shower once every four days, despite doing hard physical labour every day. The toilet was a longdrop that was so full, the faeces came right up to the toilet seat. I remember putting rocks in it to make sure the faeces did not touch me while I used the toilet.

One supervisor helped me send letters to my mother and she kept some. In one, I mention that my shoes and pants had been stolen and that I had been involved in two fights, “and one involved a knife”.

I never saw my social worker after he dropped me off at Whakapakari. He rang once and talked to a supervisor who told him I was doing well and fitting in. If he’d called me, I would have told him about the violence and abuse.

When I got home from Whakapakari, I felt overwhelmed, and struggled to fit back into society. I was never visited by a social worker or provided with any sort of support from CYFS to assist me in slotting back into life after Whakapakari. I didn’t cope.

I have intense flashbacks of the violence and it often keeps me awake at night. I feel robbed of any opportunity in my adult life, especially because I never got a proper education.

I have used alcohol extensively in the past to block out traumatic memories.

A few years ago, I was diagnosed with a degenerative brain disease. I have a lot of headaches and am on medication because of this. While it is difficult to pinpoint an exact cause, doctors have told me that most my health issues could be triggered by Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder from my time at Whakapakari.

Those three months at Whakapakari have stayed with me for life. [228]

"He knocked me unconscious and left me lying there covered in blood. The other boys were ordered not to help me or check on me. I still have multiple scars across the back of my head.”

Footnotes

[228] Witness statement of Scott Carr (7 March 2021).