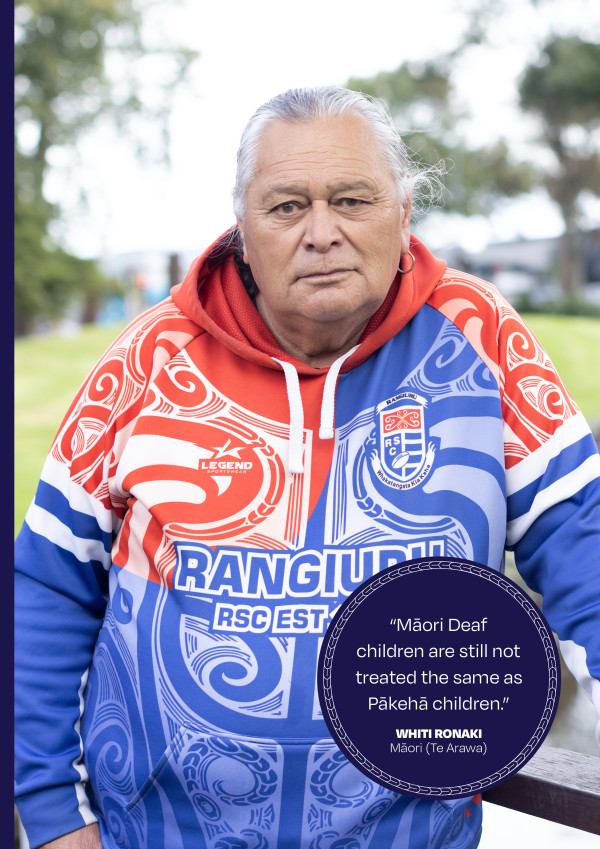

Survivor experience: Whiti Ronaki Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Whiti Ronaki

Hometown Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Age when entered care 6 years old

Year of birth 1954

Time in care 1959–1969

Care facility Kelston School for the Deaf in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Ethnicity Māori (Te Arawa)

Whānau background Whiti was an only child. He was raised by his birth mother’s cousin and his adoptive father. He has eight sisters and nine brothers to the same parents in his birth family.

Currently Whiti lives in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and does a lot of volunteer work with the Māori Deaf community. He is close to his children and grandchildren.

When I was 3 years old, I got the measles and lost my hearing.

Growing up, they called me mischief. I had difficulty understanding whānau – I didn’t understand how they were communicating with me. It was a problem. They thought I was being cheeky and I used to get hit and yelled at, but I was Deaf. My father would physically attack me, which made me so scared. He used weapons, anything he could get his hands on.

The doctor said I was Deaf, not Deaf and dumb. Because I couldn’t hear, I had to learn everything with my eyes.

I arrived at Kelston in 1959, then aged 6 years old. I was a boarder, and I was scared at the beginning. There were heaps of Deaf kids, and they were all signing. I didn’t know how to, so I sat in the corner watching and learning. Most of them were Pākehā. I was stiff, I couldn’t relax.

At dinner, I didn’t know how to use a knife and fork and a teacher hit the back of my hand with the blade of a knife. That night before bed, I learnt about toothbrushes – I had never used one before.

When I went to Kelston, sign language was banned. If you tried to sign you were strapped. You had to be oral and talk. We had to wear hearing aids. I didn’t like it. In the break, we would hide in the playground to sign, and if we saw a teacher we would stop. We learned to sign by watching each other. We made up our own way of communicating.

Even the Government banned sign language. It wasn’t fair. This made learning in the classroom hard. I didn’t know what the teacher was saying, and I wasn’t allowed to sign and ask for help. I couldn’t understand, I couldn’t see what she was saying. The teacher would growl at me – she said we had to listen. The whole class had to learn how to lip read, but the teachers didn’t know how to lip read.

It took me a long time to learn how to say hello – they said my tongue was lazy, but I was trying my best and it wasn’t fair. I had to put a feather in front of my mouth and spit on it to make it move and make the right sounds. It was very difficult.

There was no Māori culture or te reo Māori taught at school. It was the 1960s, so we didn’t have to be taught our language and culture. I was confused about my identity – I didn’t know I was Māori and Mum and Dad didn’t explain anything to me.

The staff were Pākehā. The cook was Māori. She used to take us in the kitchen and give us big bowls of ice cream. We would give her big hugs. It was just what we needed. One staff member knew she was feeding us. They would ask, “Where have you been?” It was like being in a prison cell for all us Māori.

Some staff didn’t like Māori children and didn’t treat us the same as the Pākehā children – the Pākehā kids got toothpaste, but the Māori kids got soap. They would smell your mouth to make sure you brushed with soap. I was frightened. I complained to the principal, but he didn’t believe me. The complaint failed even though I told the truth, and it was abuse.

There was a staff member that I hated, and another man too. At bath time they would use the soap and wash you for a long time then put their hands up your bum. The boys in the bath would play with each other, too. I felt yuck. The other kids would tell their parents what was going on, and they’d go to the principal, but he didn’t believe it. I think there were other kinds of abuse. We were all too scared to do anything about it.

Growing up with the abuse, I would fight with gangs, fight with whānau. It was wrong, no one taught me — not my parents, whānau, friends. I had to teach myself, and I was trouble.

I found out about my biological family when I was 18 years old. One day I asked my real dad why he gave me away. He told me to get out and closed down. He was so angry. His words hurt me, but I had the right to ask. That’s why I got into the gangs and fighting when I was young – I was frustrated with my life. I was attracted to the gangs because it was a place that I had power and mana that I didn’t have before.

When I was in the gang, the police were hard on me. I used to go to the pub on payday and I’d be drinking a jug of beer when they came in. I couldn’t communicate with them, so they would grab me and put me in the truck. I’d be confused. They’d get my cards out of my wallet to find out my name. I didn’t understand the way they communicated or the words they used. They would make up stories, like saying I pissed in the garden. I’d be charged and have to go to court. They would write a report that I didn’t understand, and there were no interpreters to communicate with me. It was all oral, and even though I tried to lip read, I couldn’t follow what was going on.

They were all Pākehā, picking on me because I am Māori. It was so frustrating and I would get angry. I didn’t know why they treated me like that.

I met another Deaf man and I told him I was in the gangs. He said, “What are you doing that for? Come to the Deaf club. You can talk, and we do fun things. We play sports, you should come.” I went to Deaf club without my patch, and I met heaps of people I went to school with. It was great talking and seeing them again.

When I left the gang life at age 25, the Māori Turi community pressured me to change. It made me relax from the police always getting at me. I did some self-reflection and realised I wanted to join the Māori Turi community to help them and the young ones. Now, I take my patch and talk to Māori Turi youth about my stories and my journey in gangs. I tell them to not get involved, to think and be careful.

I feel that Māori Turi children are still not treated the same as Pākehā children. You have to be careful when you talk to Māori Turi children. They read facial expressions, and when some of the staff yell at the children that makes them feel uncomfortable. We need to help, support and train more staff and teach good communication skills that will help the children.

My most recent job was at Kelston school as a voluntary kaumatua. I visited a 10-year-old girl at school who was always in trouble. She was shocked, as she had not met a Deaf Māori man before. She told me her teacher was Pākehā and didn’t understand Māori ways. I told the teacher and said if the teacher couldn’t teach the girl, to get a Māori staff member or someone else. They asked me to come back and volunteer one day a week.

Before I got the job, the children feared me because I was covered in tattoos. I went to WINZ and asked if I could get them removed. It cost me $20. When I got the job, the children asked where my tattoos had gone. I said they were butterflies and they flew away. I had changed – I became positive.

Some things have changed at Kelston that make it better and safer for the children. But lots of the Māori Turi children are not happy because the staff are all Pākehā. Some of the Pākehā staff are good and some are not. I tell the children that they have to accept it for now.

Due to how and what I was taught at Kelston, I was alienated from both the Deaf and the Māori communities. I couldn’t understand the Deaf community because I wasn’t allowed to learn in sign language. I was alienated from the Māori community, because I wasn’t taught any language or cultural practices that would help me understand and be able to live as a Māori man. I had to learn later in life.

There is a disconnect between Deaf and Hearing people. A long time ago my daughter wanted to be an interpreter, so she signed up for a course. The teacher was Hearing, and I objected – I told him the class should be taught by the Deaf.

I think there is also a disconnection when Māori Turi attend events on the marae. Māori sign language needs more interpreters, as not many are fluent in te reo Māori and sign language.

When I sign in Māori I include Māori concepts, and mix it with English. When I do the karakia, on the marae, I sign in te reo. It should be voiced in te reo by the interpreter – to me it doesn’t sound right to voice my karakia in English. If you visit my marae, my whare, my pōwhiri, that is my culture. When people understand that switch in thinking, they get it.

I think sign language should be adapted to represent Māori concepts and this work should be done by Māori Turi, for Māori Turi. We need to help each other and get everyone’s different perspectives.[61]

Footnotes

[61] Witness statement of Whiti Ronaki.