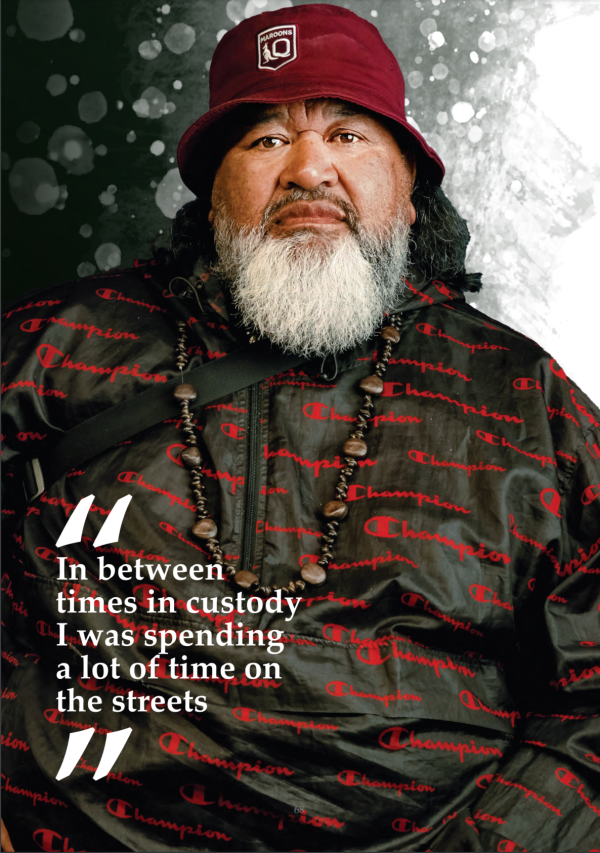

Survivor experience: Fa'afete Taito Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 14 years old

Type of care facility: Boys’ home – Owairaka Boys’ Home in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland; Youth Justice – Waikeria Borstal in near Te Awamutu

Ethnicity: Samoan New Zealander

My parents moved to New Zealand from Samoa in the 1950s with the hope that they could earn money to provide a good life for their children, to enable us to have a good education, and to send money back home to Samoa. My father was very involved in the church and we spent every Sunday attending church and helping out afterwards. My Mum loved me very much and I was always close with her. My father, like many Samoan men of his generation, struggled with the broader cultural forces at play and the challenges of trying to raise his family in New Zealand society while maintaining Samoan values. My father experienced strict discipline at home himself when he was younger so he saw that as a normal way to parent us.

When I was about 12 years old, I started running away from home when I could tell my dad was in a bad mood and I was in for a hiding.

This pattern of me being beaten by my father, running away, and then being beaten when I was returned continued. I was brought before the Children’s Board at Hampton Court in Auckland city. I remember there would be two judges, social workers, priests and members of the Police ‘J team’ (juvenile delinquent team). I became well-known to them. At school, I became more violent getting into fights with other kids. Looking back, I suppose I thought violence was normal because of the regular hidings I was getting at home.

I got sent to Owairaka Boys’ Home for the first time when I was 14 years old. I was reading the court file prepared for the social worker and it said that I had been adopted. Until then, I grew up believing that my parents were my biological parents.

When I first got taken to Owairaka, I had no idea what was happening. I was crying in the van and tried to ask the social worker why I was going to this place and not home and he said “it’s coz you’re a fucking State ward now so shut up!” One of the workers who took me into secure on my first day pointed out a Māori boy and said “that’s the kingpin. If you don’t behave here, you’ll get a hiding from him.”

At Owairaka I learned how to steal cars, how to pick locks, and I was introduced to cannabis for the first time. I wasn’t sexually abused at Owairaka but I experienced a lot of physical violence. The workers there allowed kids to bully and assault other kids. I also think, for some of them, seeing fights appealed to their sense of humour and was a form of entertainment.

I was often pushed around and abused by staff and racially insulted. The first time I was in secure I didn’t know that in the mornings they let you out for a short time to run around the yard. I was just unlocked and told to start running. When I got tired, I stopped, and they then yelled at me to keep running.

I got kicked out of high school for burglary when I was 14 years old. At that time, it was illegal to suspend or expel kids from school who were under 15 years old. In 1976 the Education Act was amended and I became the first child under the new legislation to receive an exemption order. I had a letter I kept with me for if I was stopped by authorities to show that I did not have to be at school.

I also had two stints at the borstal in Waikeria. That was a whole other level to what I had experienced at Owairaka. In Waikeria I met a lot of the kids that had been in Owairaka with me. The majority of them had joined the Mongrel Mob and Black Power and I was asked to join the Mongrel Mob by one of my mates that had been at Owairaka with me. I had heard a little bit about the King Cobras in Ponsonby, so I wasn’t sure about joining the Mongrel Mob.

When I look back on that period of my life, I see the State gifted me the gang lifestyle. In between times in custody I was spending a lot of time on the streets with other kids who were in similar situations to me. We would find abandoned houses to stay in until the police J-team came after us. In winter, we would stay under Grafton Bridge with cardboard boxes under us to sleep on and we would pinch blankets from Auckland Hospital to stay warm.

When I was about 16 years old I starting hanging out with others in Ponsonby who were the beginnings of the King Cobras. In 1979 I was sent to do my first lag at Mt Eden Corrections Facility. I was 17 years old and a fully patched member of the King Cobras. I spent 12 years as a patched member. I left the gang in 1990 but continued on the criminal pathway I was by now well accustomed to. The criminal underworld and lifestyle had become part of who I was. I could not see any other life for me.

In the 1990s, I did a seven-year stint prison sentence. I got out in 2000 but was sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment in 2001 for drug offending. I served those sentences at Paremoremo prison in Auckland. I got out of prison in 2006. I began to want to change but taking a different pathway seemed impossible to start with. In 2009 I started to change slowly but it took some time.

It took me awhile to come to the realisation that I would have to leave the criminal world altogether to fully make the change. In the end, I left and went straight for my partner. My partner has been by my side for 29 years and I wanted to make sure I was around to live my life with her and for my children. Between us we have 6 children and I wanted to be there for them.

It was incredibly hard coming off drugs with no money and no support. In 2010 my partner told me I needed to do something with my time. She encouraged me to study as she was worried if I had too much time on my hands I would end up going back to my old ways. I have now completed a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Auckland with a double major in Sociology and Māori.

With time, and through my studies, I have had the opportunity to reflect on my life and I made peace with my adoptive father and what happened in my early childhood years. There are three long term impacts that are important context to trying to understand the broader issues of abuse and neglect in care and the devastating impacts they can have for people:

- Identity – by removing me from my family, I lost part of my identity. To be taken away from my mother at such a young age had a profound and lifelong impact on me. My mother was everything to me in terms of being Samoan, being Christian, being my family. Being Samoan and being Christian were most of what I knew previously. I came out of care being tough and being violent. That was my new identity.

- Pathway to crime and prison – my family and I were not offered support at the time I was taken into care. Instead, I was removed and placed in an environment where I was moved closer towards a gang lifestyle. The number of gang members who began in boys’ homes illustrates the strong link between early abuse and neglect and a life of crime.

- Losing the ability to love – the world of State care and the gangs takes away your ability to love and care. My mother loved me but I lost the protective power of that love when I was removed and made a State ward.

Racism was alive and well in New Zealand during this time. Authority figures: teachers, police, social workers and others were predominantly white New Zealanders and many openly looked down on Pacific Islanders. The Dawn Raids exposed the overt racism that many of us experienced on a daily basis. A lot of us New Zealand born Samoans felt lost in this new society. We were not accepted by our own culture and we were definitely not accepted by New Zealand Palagi culture.

Violence within the home can be seen as a symptom of struggling with the culture shock and dislocation experienced by many Pacific Island families. However, removing children from a violent home and placing them into an emotionally and physically violent institution cannot be said to be in anyone’s best interests.

I am speaking out today in the hope that others will feel that they can come forward and share their stories. New Zealand needs to hear the truth about what happened during those years so that we can begin to heal and move forward.

Source

Witness statement of Fa’afete Taito (24 September 2019).