Chapter 2: Circumstances that led children and young people to enter social welfare care settings Ūpoko 2: Ngā āhuatanga i uru ai ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi ki ngā taurima tokoora

8. The State’s role in relation to children and young people has evolved over time. Between 1925 and the 1980s, the role and primacy of the State in ensuring child welfare was cemented. The 1925 and 1974 legislation required the State to intervene when a child’s parents were seen to be failing.[2]

9. Between the 1950s and 1970s, structural and societal factors such as racism, demographic shifts, increased moral panic about perceived juvenile delinquency, urbanisation of Māori, and increased distress and poverty experienced by families – saw more State intervention and entries into care. From the early 1980s until the early 2000s, the numbers in social welfare care dropped off and remained stable but they began to rise again from the early 2000s.

10. Throughout the Inquiry period, children and young people entered State care through the court system, after being brought to the children’s courts either by police or child welfare officers, later called ‘social workers’.[3] A minority of children and young people were placed into care at their own request or the request of their whānau.[4] The conditions that contributed to increased criminalisation of youth and as a result, their appearances before the courts, as well as the increased power of social workers, the police, and the judiciary are discussed further in chapter 2.

11. All of these factors were reflected in survivor experiences. Survivors spoke about being labelled ‘delinquent’ or ‘anti-social’ for behaviours that were in response to matters such as poverty, trauma, abuse and neglect at home, and being targeted by child welfare officers, police and other authorities, as well as what is now recognised as undiagnosed and diagnosed neurodivergence. The Inquiry heard how these matters were criminalised, and how survivors entered social welfare care through the courts.

12. Some parents were encouraged or felt they had to voluntarily place their children or young people into social welfare care. Some survivors questioned why the State and child welfare officers took them into care, instead of providing support to enable their families to continue caring for them and their siblings.

13. Many survivors spoke about experiencing abuse and neglect at home before entering social welfare care. In these instances, some form of intervention was needed to keep children and young people safe, but often the available forms of support were not fit-for-purpose or did not focus on supporting the whānau or addressing intergenerational trauma. At the same time, the way survivors were taken, and the social welfare settings they were placed into, sometimes failed to keep children and young people safe – and instead, compounded the trauma survivors had already experienced. Entries into social welfare care for Māori and Pacific survivors were shaped by the effects of colonisation, urbanisation, structural, societal, and interpersonal racism.

Tokohia i uru atu ki te tokoora pāpori

How many entered social welfare

14. During the Inquiry period most children and young people in care lived in their own homes, with extended family, or were in foster homes. Between 1945 and 1979, on average, between 40 and 50 percent of children in social welfare care settings lived in foster homes.[5]

15. Not all State wards were placed into social welfare care settings. The number of State wards shifted dramatically over the Inquiry period – rising to a peak from the 1960s to the 1980s, and then decreased.

Total State wards: children under control and supervision of the Child Welfare Division 1945–1987, and child welfare agencies 2000–2019 [6]

16. From 1950 to 1999, an estimated 178,443 people were in social welfare care settings. Of these people, an estimated 67,566 were in youth justice settings.[7]

Table 2.5. Cohort of people within Social Welfare care settings, 1950 to 1999 [8].

|

Summary by decade |

1950s |

1960s |

1970s |

1980s |

1990s |

Total |

|

Youth justice |

1,195 |

5,248 |

22,537 |

24,843 |

13,743 |

67,566 |

|

Other state-wards |

16,068 |

20,130 |

33,277 |

26,735 |

14,667 |

110,877 |

|

Total numbers of state-wards (cohorts) |

17,263 |

25,377 |

55,814 |

51,578 |

28,410 |

178,443 |

|

Source: MartinJenkins Ltd (2020. P. 27). Youth Justice included institutions administered by DSW (Child Welfare Division pre-1972) or by the Department of Justice. The decline in cohort numbers in the 1990s is more likely to be due to incomplete data, rather than a signal of a policy or operational change. |

||||||

17. In 1962, 23 percent (810) of State wards were in some form of care setting, including social welfare residences, special schools, private institutions, psychiatric institutions, hospitals and boarding schools.[9] This figure rose to 33 percent (2,306) during the early 1980s but by 1985 it had dropped slightly to 31 percent (1,807).[10]

18. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori were more likely than Pākehā children and young people to be placed in borstals and other social welfare institutions,[11] whereas Pākehā and Pacific children and young people were more likely to end up in foster placements.[12]

Ko te nuinga ko ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi Māori

Tamariki and rangatahi Māori made up the majority

19. Tamariki Māori were the majority of the thousands of children and young people passing through social welfare care settings in the 1970s.[13]

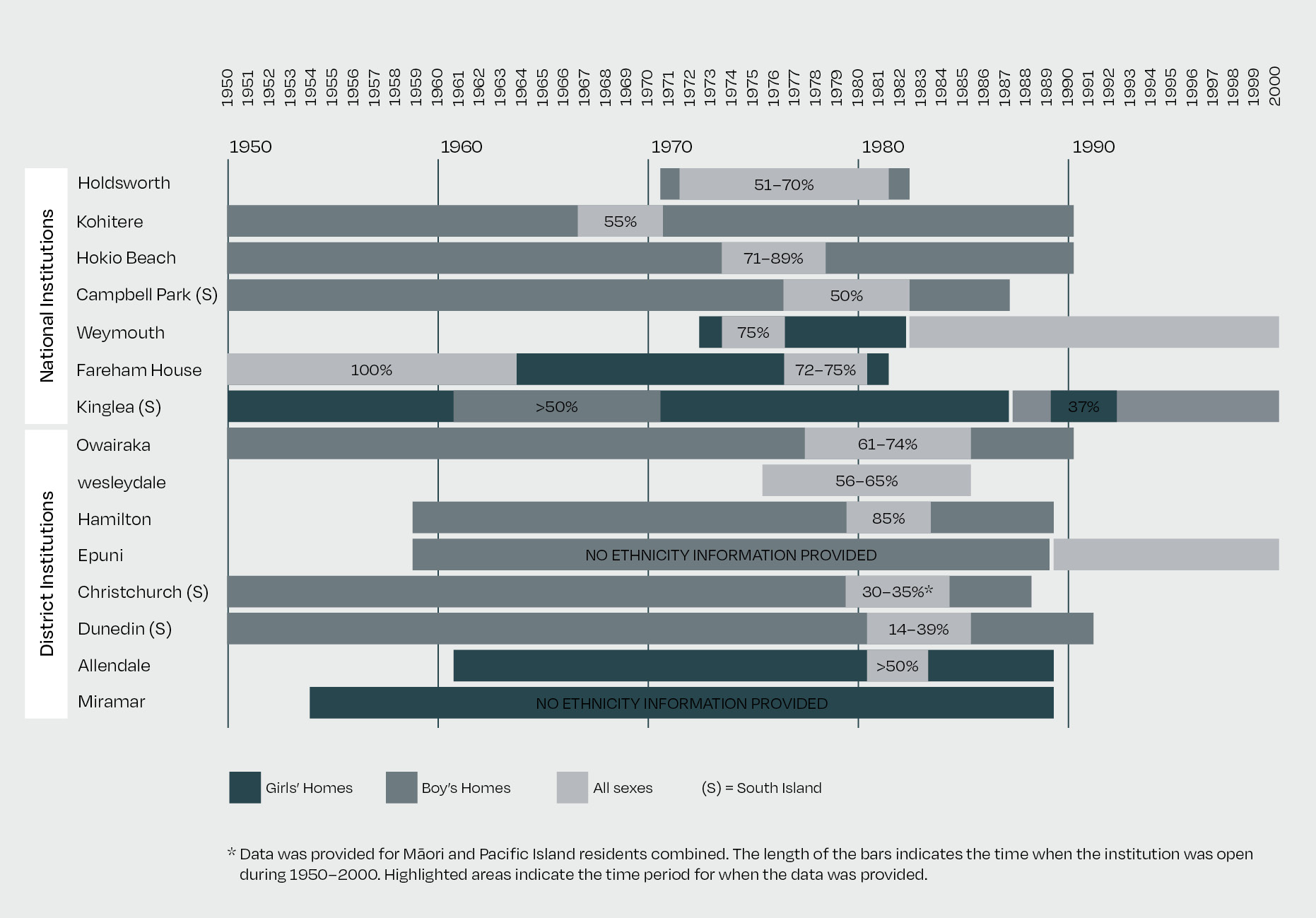

20. The number of Māori in social welfare care settings was the highest in the 1970s and the early 1980s, reaching up to 80 percent in some social welfare residences. Following the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, increased emphasis was given to placement with whānau or community. The overall number of children placed in social welfare residences significantly reduced. However, the proportion of tamariki and rangatahi Māori admitted to social welfare residences remained high.[14]

21. While many social welfare residences did not record ethnicity consistently over the Inquiry period, available information shows tamariki and rangatahi Māori were over-represented across social welfare residences (referred to in the table below as ‘residential institutions’)

Proportion of Māori residents in residential institutions collated from Parker’s (2006) reports [15]

22. Professor Elizabeth Stanley recorded that tamariki and rangatahi Māori constituted about 25 percent of the boys in Ōwairaka Boys' Home in the late 1950s and early 1960s. By the 1970s, this figure had increased to more than 80 percent.

23. In 1985, the State recorded a 78 percent Māori population across six Auckland social welfare residences: Allendale, Bollard, Ōwairaka, Te Atatu, Wesleydale and Weymouth. Epuni, Hokio Beach and Kohitere had similarly high proportions.[16]

24. A 1998 birth cohort study of 56,904 babies in Aotearoa New Zealand showed that by the age of 18, tamariki and rangatahi Māori were three and a half times more likely to experience out of home placement than Pākehā children and young people.[17]

I pāhikahika te uru o ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi Pasifika

Pacific children and young people’s entry was disproportionate

25. Data gaps exist across all survivor groups during the Inquiry period, but the gaps are particularly pronounced for Pacific Peoples. State agencies responsible for care had fundamentally flawed policies and processes for recording ethnicity. Various institutions show that Pacific Peoples were frequently grouped with Māori in a general ‘Māori / Pacific’ category, or simply under the category of ‘Polynesian’, or their ethnicity was not recorded. This reveals the systemic flaws in ethnicity recording and makes it difficult to provide a meaningful picture of Pacific Peoples representation in care during the Inquiry period.

26. The available records show that from the 1980s, Pacific fanau and tagata talavou were also disproportionately represented in social welfare residences. In 1983, Pacific Peoples were over-represented in the same six social welfare residences in Auckland referred to above (Allendale, Bollard, Ōwairaka, Te Atatu, Wesleydale, Weymouth). Of the 2,027 residents in these institutions (who were there for both welfare and youth justice reasons), 16 percent (330) people, were Pacific, despite only making up just over 6 percent of the youth population.[18]

27. An Epuni Boys’ Home report from 1975 stated that the proportion of Māori / Polynesian residents varied from 50 percent to 70 percent.[19]

Te urunga o ngā kōhine ki ngā taurima tokoora

Entries of girls into social welfare care

28. Available and reliable data on the gender breakdown of entries into social welfare care is also limited.

29. A 1984 report of the Committee to Review the Children’s Health Camp Movement presented data for children in substitute care (defined in the report as ‘looked after by other than biological parents, relatives or friends) recorded that in 1980, 1,350 children were involved in family homes with 45 percent being girls, and that 3,120 children were involved in foster home programmes with 47 percent being girls.[20]

30. Various reports and research show the disproportionality between Māori girls and non-Māori girls in care. In 1987 a study conducted on behalf of the Department of Social Welfare, looked at 239 girls between the ages of 15 and 16 who were under the guardianship of the Director-General of Social Welfare. The study found that 37 percent were Pākehā, 51 percent were Māori and 12 percent were from other ethnic groups, primarily of "Pacific Island origin”.[21]

31. Evidence the Inquiry has received also supports that Māori girls disproportionately entered care. A 1975 report from Allendale Girls’ Home has an ethnic breakdown of admissions that shows 23 Māori, three Pacific, and 12 Pākehā girls were admitted between February and April of that year.[22] This overrepresentation of Māori girls in Allendale was also recorded for the years 1981 and 1983.[23]

32. Documents from Kingslea (also known over the years as Burwood and Christchurch Girls' Training Centre) showed a disproportionate number of Māori and Pacific girls being admitted between the 1950s and the 1970s. In 1961, Kingslea had a total of 37 admissions of girls, reporting that 15 were either Māori or Pacific. In 1970 there were a total of 62 admissions, with Kingslea reporting that 36 were Māori or Pacific. The report did not differentiate between the two groups. The report also made a comment with racist undertones noting that the increase in Māori and Pacific girls “introduced new problems for training and discipline”.[24]

I whai wāhi te tāmitanga me te kaikiri ki te urunga a te Māori ki te taurimatanga

Colonisation and racism contributed to Māori being placed into care

33. The pathway for tamariki and rangatahi Māori into social welfare care settings needs to be considered within the continuing process of colonisation, urbanisation and the ongoing denial of the inherent right for Māori to exercise mana motuhake. As outlined in Part 2, before colonisation:

- Tikanga Māori was the dominant political, social, cultural and legal paradigm in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- The tikanga of whānau created a framework between tamariki, rangatahi and pakeke Māori and broader whānau, hapū and iwi.

34. Dr Moana Jackson, a witness at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing considers that colonisation’s ultimate goal is to assume power and impose legal and political institutions in places that already have their own.[25] In Aotearoa New Zealand, it means subordinating the mana and tino rangatiratanga of iwi and hapū, and deliberately undermining whānau, hapū and iwi structures.[26] Colonisation is more than just the appropriation of land.[27]

35. The effects of colonisation, along with its racist ideologies, may include removing tamariki and rangatahi Māori from whānau and denying the rights of whānau, hapū and iwi to make decisions for tamariki and rangatahi Māori.[28]

36. Similarly, in Australia, the 1997 Australian Inquiry into the ‘Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families’ discussed the connection between colonisation, removal of indigenous children, and genocide.[29] That Inquiry concluded that the predominant aim of removing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, communities and homes was for absorption and assimilation – to destroy and eliminate their unique cultural values and ethnic identities.[30] It found the laws and practices of removing indigenous children involved both systemic racial discrimination and genocide as defined by international law.[31]

“When a child was forcibly removed that child’s entire community lost, often permanently, its chance to perpetuate itself in that child. The Inquiry has concluded that this was a primary objective of forcible removals and is the reason they amount to genocide.”[32]

37. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission inquiring into Canada’s residential school system similarly found Canada had enacted cultural genocide through its Aboriginal policy, specifically its policies of assimilation. The commission found that the taking of indigenous children into residential schools was a central element to those policies.[33] Cultural genocide was defined as:

“The destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group. States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group. Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred, and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to another.”[34]

38. Dr Moana Jackson considered there to be connections between the Canadian and New Zealand governments and indigenous child removal into care, noting that the colonising governments shared the same assimilation intentions.[35] Dr Jackson said the State had assumed the same authority to take tamariki and rangatahi Māori away from their families.[36]

39. Dr Jackson noted that the State had also seized land, forcibly transferred Māori, banned te reo Māori, persecuted spiritual leaders, forbidden spiritual practices, destroyed objects of spiritual value,[37] and disrupted whānau to prevent the transmission of cultural values. Dr Jackson said the actions of the State could be “equally and properly” described as cultural genocide:[38]

“The intention to take has been the same as in other countries, and dispossession is dispossession, even when it is carried out with an allegedly honourable intent or ‘kind usage’. Colonisation has always been genocidal, and the assumption of a power to take Māori children has been part of that destructive intent. The taking itself is an abuse.”[39]

40. In 2021, the Waitangi Tribunal’s Inquiry into Oranga Tamariki found that the continued over-representation of tamariki and rangatahi Māori in social welfare care arose and persists due to alienation, dispossession, structural racism, Crown policy that has been dominated by efforts to assimilate Māori, and the Crown failure to honour te Tiriti o Waitangi guarantee of tino rangatiratanga.[40]

41. During that Inquiry, Grainne Moss (chief executive of Oranga Tamariki at the time of the Inquiry) conceded on behalf of the Crown that:

“Structural racism is a feature of the care and protection system which has adverse effects for tamariki Māori, whānau, hapū and iwi. This structural racism has resulted from a series of legislative, policy and systems settings over time and has degraded the relationship between Māori and the Crown. The structural racism present in the care and protection system reflects its presence in society more generally, which has meant that more tamariki Māori are reported, thus coming to the attention of the care and protection system.”[41]

42. Further, the Crown accepted that “the broader forces of colonisation and structural racism and the ongoing effect of historical injustices on iwi, hapū, and whānau have been significant contributing factors”[42] to the number of tamariki and rangatahi Māori being taken into care.

43. Māori survivor, social worker and advocate Paora Moyle (Ngāti Porou) has spoken about the deeply held racism in the decision-making around the removal of tamariki and rangatahi Māori from their whānau:

“We’re talking about whakapapa trauma, intergenerational trauma. We’re talking about colonisation and children being taken by the State as a result of out-and-out racist decision-making. Many of those children shouldn’t have been taken – and even now, I’m calling it out, that children are still being taken for reasons other than the need to protect that child from abuse and neglect.”[43]

Ko ngā taiao pāpori tētahi ara tōtika ki te taurimatanga

Social environments were a pathway into care

I kaha ake te Māori ki te nohonoho tāone

Increased Māori urbanisation

44. Before 1945, most Māori lived in rural communities, leading quite separate lives from the majority of Pākehā.[44] The decades from the 1930s to the 1980s saw the mass migration of Māori from rural areas to the towns and cities of Aotearoa New Zealand. Between 1936 and 1945, the percentage of Māori living in urban areas grew from 11 to 26 percent. In 1966, at the peak of Māori migration, 62 percent of Māori were living in urban centres.[45]

45. Māori survivor Michael Katipa (Waikato Tainui) shared that his whānau came from Ngaruawahia, where they were traditionally a royal whānau and his grandfather owned Māori land:

“We lived in a house with no power, but we were self-sufficient in gathering kai and living off the land. We never went hungry. Our whānau drifted from a more rural setting to the city due to urbanisation and Rogernomics policies.”[46]

46. The Māori population was also growing rapidly during this period and had a younger demographic profile than non-Māori. By the mid-1960s, half of all Māori were under 15 years old.[47] Urbanisation and the growing birth-rate post the Second World War were seen by some to threaten the dominant Pākehā population.[48]

47. To some degree, this urban migration was fuelled by younger Māori escaping perceived and actual deprivation in their local communities and seeking new opportunities in towns and cities.[49]However, the poverty of rural Māori communities during this period, lack of job and education prospects, as well as the novelty and excitement of city life, were also factors in the mass urban migration of Māori.[50]

48. Living in urban areas, in close proximity to Pākehā, intensified the pressures on Māori to assimilate to Pākehā ways of living. Māori patterns of child-rearing and whānau and hapū life came under strain in the suburbs, causing them to disappear or be adapted.[51] The general public expected Māori to conform to ‘British ways’. Child welfare officers who had the broad mandate of ‘bringing urban Māori up to scratch’, were frequently called in to address Pākehā complaints of ‘unseemly’ Māori behaviour from their neighbours. Tikanga Māori was often foreign and unsettling to many Pākehā families living in towns.[52]

49. The 1960 Hunn Report, which in the Inquiry’s view was founded on the belief that Māori who had been oppressed by State policies were responsible for the challenges and inequalities they faced, found that the urbanisation of Māori communities was central to settler state policies of integration into Pākehā society.[53]

50. Former government statistician, Len Cook, described how the urbanisation of Māori led to a shift in the chances of ending up being scrutinised by child welfare officers and the court system:

“I think one of the things we ignore, particularly during the 1960s is that as a result of both increased birth numbers and the shift to the cities of Māori at that time, there were four times as many Māori children in urban New Zealand in 1966 than 1951. It might have seemed to public services as quite a flood. And I think because the cities were overwhelmingly white, you had [Māori] people who, although it was their country, were migrants in their own cities, but not being treated as NZ European children were.”[54]

51. Migration to urban areas made housing and employment problems worse for Māori. It also highlighted racial, economic and social inequalities and influenced the social attitudes of many Pākehā towards Māori. Welfare issues were increasingly identified by officials in both urban and rural Māori communities. Explanations for these welfare problems included Pākehā racial prejudice against Māori, intolerance and ignorance of Māori custom, as well as poor employment opportunities, substandard housing, and the breakdown of traditional Māori structures and other ongoing impacts of colonisation and urbanisation.[55]

52. The Government’s housing policy from 1948 of ‘pepper-potting’ Māori whānau among Pākehā was to avoid residential concentrations of Māori as there had been concerns and complaints about social disorder and a ‘growing Māori underclass’.[56]

Nā te kaikiri i whakakaha ai te maurirere matatika me te tūtei rangatahi

Moral panic and surveillance of youth compounded by racism

53. From the early 1950s the increasingly youthful nature of the population, rising rates of reported youth crime, and the emergence of youth culture in suburbs and cities, heightened public anxieties about a growth in so-called ‘juvenile delinquency’.

54. Societal fears over the behaviour of young people were symptomatic of wider societal unease about ‘adolescent independence, gendered social shifts, and weakening family control’.[57] Fears were particularly amplified following the release of the 1954 Mazengarb Report.

55. This resulted in more intensive policing of children and young people using broad categories such as being ‘Indigent’, ‘Not Under Proper Control’ and ‘Delinquent’ and contributed to the growing numbers of children and young people appearing before the courts particularly over the next two decades.[58] The majority of survivors who engaged with the Inquiry entered care around this period.

56. Professor Elizabeth Stanley explained that girls were held to a different moral standard than boys. They would come to the attention of State authorities for things like running away, staying out, or behaving in a way that was judged as being sexually promiscuous.[59]

57. During this period, the targeting of Māori and Pacific Peoples became commonplace with police officers more likely to intervene with Māori and Pacific youth. [60]

I āta whāia ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi Māori

Tamariki and rangatahi Māori were targeted

58. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori often came to the notice of State authorities, including NZ Police, for ‘potential delinquency’ rather than for their welfare.[61]Police tended to treat gatherings of rangatahi Māori on the streets as inherently suspect, whether or not they were involved in criminal activity. This often led to rangatahi Māori appearing in court.[62]

59. In the report Puao-te-Ata-Tū, a participant who spoke to the Māori Perspective Advisory Committee said that rangatahi Māori in Lower Hutt were often picked up by NZ Police for being on the streets.[63]

60. Survivors told the Inquiry they were targeted and picked up by the police, for simply being out in public.[64] Māori survivor Mr IA described how a ‘hit squad’ of NZ Police would travel from Ōtaki to Palmerston North to round up boys on the street, beat them and throw them in cells. The boys were all aged around 15 or 16 years old. Mr IA said:

“We would hang around town, sometimes get up to mischief, all male, all Māori but not a gang. We would go to the pictures on Friday nights and be hanging out and just be picked on and picked up by the police. We were shit scared of the police because we got the bash every single time.”[65]

61. In the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing, NZ Police Commissioner Andrew Coster acknowledged that Māori are disproportionately represented across the criminal justice system. He accepted there are serious questions to answer in relation to both Māori and Pacific Peoples' experiences of policing.[66] Deputy Police Commissioner Tania Kura acknowledged that views held within New Zealand Police reflected dominant views held within society, such as racism.[67] Despite this, when asked about the historical culture of the NZ Police, and whether that culture did serve to scale up the level of racism, Commissioner Coster stated, “I really can’t speak to that ... I simply can’t say that”.[68]

62. During the Inquiry period, State authorities and wider society were particularly concerned about what they saw as wāhine Māori behaving immorally. This shows the intersection between racism, sexism, and discrimination that Māori wāhine[69] had to face. In a 1967 letter a senior child welfare officer described ‘difficulties with adolescent Māori girls’, encouraging their placement into care because they were perceived as out of control and promiscuous:

“It is a matter of the deepest concern to us that in Hastings there is in recent months a growing number of young girls becoming involved in, staying away from their homes and schools, getting into most undesirable company and, it would seem, indulging in quite extensive sexual misbehaviour. The Maori [sic] children in Hawke’s Bay who belong to the less able families are increasingly showing this sort of insecurity – full of energy but no worthwhile channels available for it – mothers working long hours, they are left to their own devices. They are not involved in the sort of out of school activities the more able Maori [sic] families and the Europeans provide, and the natural gregariousness of these children sends them off to seek their own sort of company.”[70]

63. Professor Elizabeth Stanley has explained that girls who upset gendered norms and Māori and Pacific children who “offended Pākehā sensibilities” often found themselves “inspected by authorities who readily legitimised institutionalisation as a means to domesticate, civilise or control them.”[71] This impacted wāhine Māori two-fold and is reflected in the disproportionate numbers of wāhine Māori who entered care.

64. The district child welfare officer’s response acknowledged the issues raised and attributed it to the “relocation of so many rural Maoris [sic]”.[72] They also expressed frustration that the department had “insufficient foster homes or institutional facilities to deal effectively with these girls who [were] obviously beyond parental control”.[73]

65. Some whānau came to the attention of State authorities following complaints from neighbours.[74] Māori and Pacific survivor Te Enga Harris was uplifted from the care of her whānau after a complaint, “My father was Deaf and there was always a lot of yelling and screaming so he could hear us.”[75]

66. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori may have already been under the State’s scrutiny because other whānau members had experienced State care themselves, or because a young person in the whānau was under a supervision order, meaning child welfare officers started monitoring the wider whānau, sometimes for extended periods of time.[76]

67. A 1985 submission to the Puao-te-Ata-Tū Report authored by a senior Department of Social Welfare official, acknowledged the long legacy of harmful social work interventions in Māori communities:

“I think back to my beginning days as a young social worker in early 1950 when the term ‘body-snatcher’ was quite prevalent. It was quite common for youngsters and particular Māori children to be at risk in the sense that the system all too readily removed Māori children from their homes and communities and put them here, there, and everywhere but more often than not, into a Pākehā foster home and many ways and on many occasions, alienated those children from their parents and families and their families from them and in looking back all I can say is, what a heinous thing we did in those years and that’s not so very long ago and some of those children’s children are now repeating the process.”[77]

68. Ultimately, State authorities’ reactions to the behaviours and circumstances of tamariki and rangatahi Māori determined whether they were removed from their home. At times, it appears that the authorities’ responses were influenced by discriminatory or racist attitudes.[78] Research shows that rangatahi Māori were over-represented in social welfare care settings, recording that tamariki and rangatahi Māori were “more likely to be brought to the attention of the State, more likely to be criminalised, more likely to be taken into State care for less apparent risk, more likely to be placed in harsher environments, and less likely to receive intensive support while in care than Pākehā children”.[79]

Ko te Māori e tinga ana kia tū i mua i ngā kōti

Māori more likely to appear before the courts

69. Between 1950 and 1974, the number of children and young people appearing in the children’s courts increased from less than 2,000 to more than 13,000 per annum.[80] Rangatahi Māori were appearing in court in large numbers and were more likely to appear than non-Māori young people, regardless of gender.[81]The 1982 Joint Committee on Young Offenders found that 35 percent of Māori boys born in 1957 had appeared before the Children's Court by the age of 17 years old, compared to 11 percent of non-Māori boys.[82]By the early 1990s, Māori made up an estimated half of all young people involved in the youth justice system.[83]

70. The Inquiry heard from many Māori survivors who went through the youth justice system, that they had suffered from undiagnosed learning disabilities, including neurodivergence.

71. Once convicted, tamariki and rangatahi Māori were disproportionately sentenced to more punitive social welfare care settings, such as borstals, compared to non-Māori. Dr Oliver Sutherland stated:

“It is very clear that Māori children received heavier sentences than non-Māori children. Any Māori child before the court was more than twice as likely to be sent to a penal institution (detention centre, borstal or prison) as a non-Māori child, while the latter was more likely to be fined or simply admonished and discharged.”[84]

72. NZ Police Commissioner Andrew Coster accepted at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing:

“There are a disproportionate number of Māori boys who went to court and sadly that continues to be the circumstance in the criminal justice system today.”[85]

73. Mr Coster also stated that a focus of policing “is about trying to dig into what is the reason for the disproportionate representation and what role NZ Police might have”.[86]

74. Māori voices from Puao-te-Ata-Tū described how some of the youth justice cases that saw tamariki and rangatahi Māori entering the social welfare system through the courts were for extremely low-level, even trivial offending.[87] A foster carer in Kaitaia, reported experiences of tamariki and rangatahi Māori being taken to court after being accused of offences as minor as shoplifting a bar of soap. Another child she fostered was sent to a boys’ home after stealing 75 cents in a changing room (a little over two dollars in modern currency).[88] A court aid attendant similarly told the Māori Perspective Advisory Committee in 1985 that in some cases tamariki and rangatahi Māori were brought to court for ‘ridiculous’ matters that “could be easily sorted out of court”.[89]

I āta whāia te hunga Pasifika

Pacific Peoples were targeted

75. Expert witness, clinical psychologist and Associate Professor Folasāitu Dr Apaula Julia loane has extensive experience working with Pacific fanau (children) and tagata talavou (young people) and tamariki and rangatahi Māori in social welfare care settings and spoke at the Inquiry’s Tulou, Our Pacific Voices: Tatala e Pulonga (Pacific People's Experiences) Hearing. She noted racism and negative experiences with migration, among other contributing factors that led to State intervention:

“Some survivors spoke about their negative experiences with migration that included racism, poverty, loss of identity and cultural belonging. Many survivors also reported negative experiences in education such as language barriers, bullying by teachers and feelings of isolation leading to their noncompliant behaviour.”[90]

76. Samoan survivor Fa’amoana Luafutu came to Aotearoa New Zealand at 8 years old and within two years was before the Children’s Board and placed into social welfare care. Fa’amoana explained some of the difficulties faced by his family after migrating:

“When my family first arrived, we needed support to adapt to the New Zealand way of life, not judgement and expectation that we just fit in straight away. My parents’ dream of a better life collided with the cultural ignorance of mainstream New Zealand in the 1950s and onward.”[91]

77. Pacific communities experienced heightened State surveillance and racial discrimination, particularly from the NZ Police, increasing the likelihood of Pacific children and young people subsequently entering State care.[92]

78. Although Pacific Peoples were actively encouraged to immigrate to fill low-paying, low-skilled jobs, this changed during the economic downturn in the early 1970s, where “Pacific People were targeted as illegal immigrants in New Zealand and were seen to be threatening the rights of ‘New Zealanders’ to jobs”.[93]

79. For Pacific survivors, over-policing was particularly evident during the Dawn Raids period of 1974-1976.[94] Pacific survivor Mr TY shared that while walking home in his school uniform, he would be stopped by NZ Police and asked about the number of people living in his home and whether any of them arrived in the country recently. He said that the blatant targeting of Pacific Peoples was a normal thing in Ponsonby.[95]

80. Samoan survivor David Williams (aka John Williams) said he was picked on by NZ Police for no reason:

“I could be walking down the street and police would just pick on me. I would be with two white fellas and if there were two of us darkies, the cops would pull us up and leave the white guys alone. That’s what it was like … it got to the stage where I think because I was being picked up so many times by the police and labelled a criminal, it became normal.”[96]

81. During the Dawn Raids, Pacific children were sometimes held in NZ Police cells while parents and caregivers were processed as overstayers. These circumstances were sometimes a pathway into social welfare care settings for young Pacific Peoples.

Ko ngā take hāpori me ngā take ā-whānau he ara ki te taurimatanga

Community and whānau circumstances were a pathway into care

82. In explaining their experiences before care, many survivors spoke about the struggles of their families and parents, including poverty, mental distress, substance abuse, as well as events such as deaths or divorces that broke down whānau and saw the intervention of the State. Some survivors told the Inquiry about abuse and neglect they suffered from whānau before entering care, sometimes at extreme levels. Some survivors told the Inquiry this was linked to parental distress, intergenerational trauma and substance abuse, while other survivors did not know why their parents were abusive.

83. The Inquiry heard from approximately 1,331 survivors whose first entries into care were social welfare residences.[97] Of those, 63 percent reported entering social welfare care due to:

- troubled behaviour (24 percent)

- unsafe environments including abuse at home (19 percent)

- neglect by parent/s (9 percent)

- unknown (6 percent)

- parental death or separation (3 percent)

- or crime (2 percent).[98]

84. Twenty percent of the 1,331 survivors reported entering through voluntary placement by parents due to:

- parents not being able to manage caring for their child (6 percent)

- unknown (4 percent)

- survivors reporting they were unwanted by their parents (3 percent)

- troubled behaviour of children (3 percent)

- parental death or separation (2 percent)

- parents with mental distress (2 percent).

Te pōharatanga me te whakapāwera ahumoni

Poverty and financial hardship

85. Many survivors describe hardship, housing insecurity and poverty, which contributed to them being taken or placed into social welfare care settings. Pākehā survivor Mr EH, who was born in Māngere and was one of 14 children, described the poverty and neglect he faced before being placed into care at 5 years old. His father was an alcoholic and was not often working and he had an absent mother. He recalls struggling for his basic needs:

“I remember all the kids had to sleep in one bed, but there were not enough blankets. I have one memory from when I was very little of running around with no clothes on, just a singlet.

I don’t remember anything violent happening at home. We must not have had much food. I used to eat out of the horse trough owned by our neighbour. I would see him going to feed his horses and I would try and beat the horse to the food. It would be scraps of apples and cucumbers.”[99]

86. The Inquiry heard of instances where survivors stole in order to support their whānau. Māori survivor Mr HS (Ngāti Kahungunu) entered care after being caught stealing food to support his whānau. His father was hospitalised and sent home with no support, and because he wasn’t working, they couldn’t afford food:

“Despite being only 13 years old I took on the role of caring for my father, cooking and looking after him and my brothers because there was no-one else to do it. When I was 14 years old, I started stealing food to feed our whānau and I was caught and sent to Epuni Boys’ Home. I was there for about 11 months during which time my father passed away.”[100]

87. Often the only jobs Pacific Peoples could get were low paying, labour intensive and with long hours. This affected how children and young people could be cared for and meant they were left alone and / or responsible for the care of their younger siblings.[101] Some Pacific children and young people resorted to stealing food because they were hungry, and this led to them coming to the attention of State authorities.[102]

88. Māori (Ngāpuhi), Niuean and Tahitian survivor Mr VV was left at home alone as both of his parents had to work to pay for necessities, which meant they did not have time to constantly supervise him. The State became involved:

“I feel like I was taken away from home for nothing, because I wasn't going to school. Sometimes I blame my mother, but then I think to myself, what else could she do? My parents both had to work to pay the mortgage and buy a car and feed us.”[103]

89. Māori / Cook Islands survivor Mr UU (Ngāpuhi) went into care from a home environment where his grandparents had a lot of children to care for. His teachers observed that Mr UU had no lunch at school and was stealing food, so it was clear that the whānau needed wraparound support but didn’t receive it. NZ Police laid a complaint against his grandparents, which led to him being placed with an aunt and uncle. He described this placement as “a big turning point” in his life, as he got “the meanest hidings” there. Mr UU said:

“I can’t imagine how scary, intimidating and shameful that would have been for them. It feels to me that the police complaint made my grandparents feel like the only option was to give me up. The reports say it was a family decision to put me with my aunt and uncle, but my family would have felt very pressured. I know that culturally it would have been hard for my grandparents to deal with the police, and they would do anything to get rid of them because they were scared and ashamed.”[104]

90. Child protection is also an economic and political issue rather than just the behaviour of individuals and families.[105] Research shows a clear relationship between poverty and care system contact.[106] Compared to children and young people in the richest fifth of local areas, those in the poorest fifth areas have 13 times the rate of ‘substantiation’ (a finding by officials that abuse has occurred). They are also six times more likely to be placed out of whānau care.[107]

91. Recent evidence suggests that inequity is compounded by racism and bias within the social welfare care system. Racism and inequitable wealth distribution also means it is common for whānau Māori to be concentrated in deprived communities.[108]

Ngā mātua whaiora

Parents with mental distress

92. The lack of adequate support for intergenerational trauma, mental distress or disability led to instances of substance abuse and addiction, parents splitting up or divorcing and lack of parenting skills. Many survivors spoke about these dynamics affecting their parents and their households before they entered social welfare care.[109]

93. Survivors described their parents struggling to care for them and their siblings, and how responses from State authorities were often to take them away instead of support them to stay. Māori survivor Waiana Kotara (Ngāti Hako, Ngāti Maniapoto)told the Inquiry how her parents split up when she was 7 years old, leaving her mother struggling with the challenge of raising 11 children including caring for Waiana’s brother who had a learning disability. Her mother asked the doctor for help but received no support other than some prescription drugs, and she continued to care for Waiana’s brother. Without adequate support social welfare became involved due to safety concerns and permanently removed her brother from the whānau.[110]

94. Waiana’s mother had a breakdown and was placed into Sunnyside Hospital. While she was in care, Waiana and her siblings were placed in different social welfare residences and remained in care long after their mother was released from the hospital.[111] Waiana reflected:

“Looking back, I think that the system didn’t see her struggle. They just saw what they wanted to see – ‘abuse’ – and decided the only answer was to take her children.”[112]

95. The Inquiry heard from many survivors whose mothers were experiencing mental distress, which affected the functioning of the home.[113] There was often inadequate support provided to these mothers, and some were institutionalised or too unwell to care for their whānau, resulting in children and young people going into care.[114] Māori and Tokelauan survivor Mr TH (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei) spoke of how his mother struggled with her mental health while in prison, where her baby son (Mr TH’s eldest half-brother) was taken away from her and adopted out:

“The stress of it caused her to become sick. I don’t remember us ever receiving any support in relation to Mum’s mental health. While Mum was in and out of hospital, Dad couldn’t cope with us. Because of everything that was happening at home [including abuse], I started playing up, missing school and running away from home.”[115]

96. Expert Dr Sarah Calvert told the Inquiry’s Foster Care Hearing that parental mental illness is universally known to be one of the primary reasons why children move into care.[116]

Te tūkino me te whakahapa i te kāinga

Abuse and neglect at home

97. The Inquiry heard from survivors that they experienced physical, psychological and sexual abuse at home, as well as all forms of neglect. This was sometimes severe and happened across long periods of time. Sometimes survivors spoke about being abused by non-family members, instances which still impacted them and influenced their entries into care.

98. Survivor Kamahl Tupetagi explained that his life with his parents was abusive and difficult:

“As well as the parties and drinking, there was lots of abuse during that time. I had a lot of physical abuse between the ages of about three and six. I was also sexually abused by people who would come and go at the house during parties and drinking.”[117]

99. Asian, Niuean, and Māori survivor Jason Fenton (Ngāti Whātua, Ngāti Kuri)described the violence and abuse he suffered at the hands of a stepfather and how this compounded other challenging factors in his life, such as the effects of suspected foetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Jason went into foster care as respite after a family tragedy, and later a youth justice facility and Whakapakari:[118]

“I can never forget the violence, the beatings, the yelling and the abuse. I had learning difficulties at school; being beaten up at home affected my brain so I had difficulty concentrating.”[119]

100. In some families, parents and caregivers’ intergenerational or unaddressed trauma contributed to the stress factors or dysfunction present in the home. Some survivors’ parents grew up in abusive environments and had their own trauma that they had not always dealt with, including from their own experiences in State and faith-based care.[120]

101. Parents’ or caregivers’ harmful alcohol or substance use, sometimes representing their own coping mechanism, was a common experience the Inquiry heard from survivors and increased the likelihood of harm being perpetuated in the home – for example, domestic violence or physical neglect. It also increased the likelihood of survivors being exposed to unsafe environments where they experienced abuse from non-family members.

102. Pākehā survivor Ms OH explained how her mother used to get angry and violent towards her and also took her to places where there “was a lot of heroin, drug addicts and men around.” Ms OH’s reports show she was sexually abused at 3 years old, before entering care.[121]

103. Alcohol use and alcoholism, particularly from fathers, often coincided with neglect. Pākehā survivor Grant Caldwell spoke about his father being an alcoholic and depriving him and his siblings of basic necessities such as food and clothes.[122]

104. Similarly, Pākehā survivor Mr EH explained that his father was a “drinker” and that there was never enough blankets and food:

“I used to eat out of the horse trough owned by [sic] our neighbour. I would see him going to feed his horses and I would try and beat the horse to the food.”[123]

105. For some survivors, their parents also experienced mental distress and / or disability as an impact of their own abuse, and particularly if they did not receive support for this harm.

106. Stress factors were further amplified for Māori, who were faced with the direct and compounding impacts of colonisation and urbanisation (including the cumulative impacts of assimilation and dispossession, intergenerational deprivation and trauma), with the State’s intentional breakdown of Māori authority and social structures, and with institutional and personal racism.[124]

107. Māori survivor Te Aroha Knox (Ngāpuhi) spoke of the trauma her parents carried through from their own upbringing. Her parents were violent towards her and her siblings:

“In our childhood we were exposed to the darker parts of our parents, watching them deal with their trauma through violence.”[125]

108. In some cases, the State had valid reasons for intervening, particularly when children were being abused or neglected. Often however, State authorities only acted once the child or young person’s behaviour became the problem, while the deeper root causes of that behaviour were not addressed.[126]

109. Survivors shared that some social workers, teachers and NZ Police failed to act appropriately when they received allegations or notifications of abuse, as well as ignoring or disbelieving survivors’ own disclosures.[127] As a result, these survivors continued to live at home in abusive or neglectful situations for longer periods of time.[128]

110. Māori survivor Ms NN (Ngāti Porou) who was abused and neglected as a child at home, told the Inquiry that she spent most of her childhood being shuttled around different places, supervised by social workers but was not removed from her home until she was admitted to Porirua Hospital for overdosing at the age of 12 or 13 years old:

“Looking back on that time, I really struggled with the fact that nobody was listening to me, and nobody did anything when I did say something. Even though I talked about what was going on, each time I got picked up from running away I was always taken back to my mother. Things with my mother got really, really bad. She had all these different men coming through the house.”[129]

Ko te whiunga mō te auhitanga he ara ki te taurimatanga

Punishment for distress was a pathway into care

111. Survivors told the Inquiry how the conditions they were experiencing at home, and sometimes at school, affected their behaviour. Poverty, parental addictions and mental health challenges, abuse, neglect and undiagnosed and unsupported disabilities frequently resulted in children and young people ‘acting out’. Often challenging behaviour drew the attention of teachers, social workers and police. Some survivors commented that nobody inquired more deeply into why they were behaving in a particular way or asked them what was going on in their lives or at home.[130] Others told the Inquiry that their earlier disclosures of abuse or neglect were ignored, and State authorities instead took action in response to behaviour they deemed to be problematic.[131]

112. People who are abused or neglected as children are more likely to experience mental distress, have trouble developing relationships, and may engage in risk-taking behaviours such as harmful alcohol and substance use.[132] In this way, social welfare issues overlap. Children and young people were often placed into social welfare care, rather than supported to deal with the stress factors they were experiencing.[133]

113. Māori survivor Mr KN (Ngāti Porou) was apprehended for low-level offending and a complaint was made against his father (his biological grand-uncle caring for him through a whāngai arrangement) for not having ‘adequate control’ over him. His records note that his home environment was not stimulating, and while Mr KN recalls it wasn’t perfect, there was a lot of aroha and affection:

“The things they lacked, such as money and support, could have easily been provided while I stayed in the home rather than ripping me out of the home and into a series of abusive environments.”[134]

114. Māori and Pacific survivor Te Enga Harris remembered the day she and her siblings were removed by the State rather than her mother being offered more support for working through her mental distress:

“I have relived this day over and over in my head. My mother was a kind and gentle woman. There was no need to treat her that way and she certainly did not deserve to be handcuffed. The police assaulted my mother that day and for that I can never forgive them. One day we had a mother and then she was gone.

“My mother needed help with eight children and therapy for her grief. I strongly believe her condition would have worsened significantly by being taken away from all her children. Rather than the State providing her with the help she needed she was punished further.”[135]

115. Unaddressed or ineffectively addressed mental and emotional impacts of adversity experienced at home could also influence the behaviour of children and young people.

116. Samoan survivor Mr TY was 12 years old when he ran away from his abusive home and lived in a tree hut for three months. A friend brought him food and when Mr TY was desperate, he took milk money from milk bottles outside houses to buy food. He was picked up by NZ Police after he was found walking along the road with a blanket, and was later charged with ‘Not Being Under Proper Control’ and was taken to Ōwairaka Boys’ Home in March 1975:

“After reading my file so many years later, I realised that I was charged with 'Not Being Under [Proper] Control' for running away from my abusive household. I had told the police that I took money from milk bottles to survive so they also charged me with theft.”[136]

117. ‘Acting out’ or running away was sometimes how survivors expressed not being heard or listened to or feeling unsafe and unsupported. Sadly, these behaviours also increased the likelihood of children and young people coming into contact with State authorities, including the youth justice system.[137]

118. Professor Elizabeth Stanley’s book, Road to Hell, is based on the experiences of 105 former State wards.[138] Eighty-seven percent of Dr Stanley’s participants came from homes where stress factors were prominent.[139]

119. Nearly half of the participants in Dr Stanley’s study came into contact with State authorities through offending (generally theft or property offences or, less commonly, violent offending), while one-third entered social welfare care through the vaguely defined category of ‘delinquency’, which might include antisocial or ‘unfavourable’ behaviour.[140]

Ngā whanonga me te tamōtanga

Behaviour and truancy

120. The behaviour of some children and young people at school, including acting out and truanting, also brought them to the attention of State authorities. It could result in an investigation and State intervention into the lives of children and young people. At the extreme, this intervention could be in the form of them being taken into social welfare care.

121. Children and young people who were trying to cope with trauma from abuse and neglect at home were sometimes labelled as naughty or delinquent at school. Furthermore, inadequate support for them or their whānau further affected their behaviour.[141] Māori survivor Neta Kerepeti (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Mutunga) said she became rebellious in response to sexual abuse:

“I was a bully. I didn’t want to be at school. I started wagging school and smoking pot. Truancy was a big part of me getting mixed up with the authorities.”[142]

122. Pākehā survivor Grant Caldwell described how his father entered into a voluntary agreement to place him into a social welfare institution, when he was 12 years old after he threatened a teacher:

“Looking back, I was a young child dealing with a lot of trauma. I was dealing with poverty, my father’s alcoholism, neglect and isolation. I think this event was a cry for help. I believe that all these factors are what eventually led to my placement in State care.”[143]

123. These experiences in school were compounded for survivors who today might be diagnosed with neurodiversity, such as autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and foetal alcohol syndrome, a head injury, or being hard of hearing or a person with vision impairment.[144] Factors like these that can affect survivors’ ability to learn. For much of the Inquiry period these diagnoses were not recognised or poorly understood and therefore not appropriately supported in either the school or home environment.[145]

124. Some survivors who immigrated were not offered support to learn English, which led to difficulties at school and their subsequent entry into care.[146] Survivor Fa’amoana Luafutu arrived from Samoa without speaking English and found it difficult to cope at school as he couldn’t understand what was going on. This caused Fa’amoana to start truanting, along with his cousins:

“That’s how we first came to the attention of the State. It was deemed that we were out of control.”[147]

125. Acting out or having challenging behaviour, for the various reasons explained, also resulted in children and young people being moved between social welfare settings.

Ngā ara ki ngā momo whakaritenga taurima tokoora

Pathways into different types of social welfare care settings

Ngā whare taurima me ngā kāinga whānau

Foster care and family homes

126. As mentioned, between 40 and 50 percent of children in care lived in foster homes during the Inquiry period. From the mid-1950s children in care were also placed in family homes, which catered for children who were considered difficult to foster but for whom a social welfare residence placement was unsuitable.[148] Foster care was used mainly for long-term placements, while family homes were generally used for short-term stays.[149] NZ European and Pacific children and young people were more likely to end up in foster care,[150] while tamariki and rangatahi Māori were more likely to be placed in more restrictive environments like social welfare institutions and family homes.[151]

127. Government policy caused ethnic inequality within foster care placement, “as placement schemes were not designed for Māori foster parents, or Māori tamariki”.[152] Pākehā were often reluctant to foster tamariki and rangatahi Māori, which led to more tamariki and rangatahi Māori ending up in social welfare institutions and family homes.[153]

128. Beginning in the 1950s, ‘kin placements’ were paid at a lesser rate by the Child Welfare Division resulting in fewer Māori foster homes being available, and tamariki and rangatahi Māori often being placed with Pākehā foster parents.[154]

129. Later in 1979, the State introduced the Intensive Foster Care Scheme. This aimed to provide foster placements for children defined as ‘difficult’ and harder to place in conventional foster homes, but also allowed foster parents to express preferences for ethnicity.[155] Seventy-seven percent of the conventional foster care parents did not have an ethnicity preference for the child, compared to 57 percent of the Intensive Foster Care Scheme foster parents. More than a quarter of the Intensive Foster Care Scheme parents preferred to foster only Pākehā children.[156]

130. While the recruitment process was not entirely clear, applicants wanting to foster through the Intensive Foster Care Scheme were assessed against criteria that appeared to uphold Pākehā ideals about family and home life. The questions assessed the skills, confidence and knowledge about dealing with children’s behavioural and developmental issues, however, cultural competence was not taken into consideration.[157] This meant that potential whānau Māori were sometimes denied the opportunity to foster through this scheme, as they were not seen to reflect the idealised family structure or physical home environment.[158]

131. Some Māori survivors told the Inquiry that the State would not allow them to live with whānau who were willing to take them in, including aunties, uncles, and grandparents. Māori survivor Ms NN told the Inquiry her aunt fought for her for a long time but was unsuccessful:

“I have thought a lot about why I couldn’t go to my Aunty. My uncle worked and my cousins were well looked after. She is Māori and it is hard not to wonder if that had something to do with it."[159]

132. Oranga Tamariki Chief Executive Chappie Te Kani acknowledged at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing that the care and protection system between 1950 and 1999 did not have the legislative or policy settings to ensure sufficient emphasis was put on considering alternatives before placing children in State care:

“This included not always providing support to families in need and not always working with extended family, whānau, hapū and iwi to support them to care for their tamariki safely and choosing to place some tamariki with non-kin caregivers rather than exploring family options.”[160]

133. In 1983, Maatua Whāngai was launched by the departments of Māori Affairs, Social Welfare and Justice in partnership with Māori communities. Social workers were designated as Maatua Whāngai officers and worked with Māori Affairs staff to find more Māori foster parents.[161] It quickly expanded into a community-based preventative scheme with iwi funded and, supported by the Government to place tamariki and rangatahi Māori in need of alternative care, regardless of their involvement with the Department of Social Welfare, into homes within their own wider whānau, hapū and iwi networks.[162]

134. Maatua Whāngai drew on the traditional Māori practice of whāngai that involved tamariki and rangatahi Māori being cared for and nurtured within their extended whānau. The objective of the Maatua Whāngai programme was to stem the flow of tamariki and rangatahi Māori into social welfare care settings.[163]

135. Some survivors shared that they had positive experiences in Maatua Whāngai placements which incorporated te ao Māori and tikanga into their care, including caregivers making them “feel valued” and like they “could be a child in their care”.[164] Others had mixed experiences,[165] or solely negative[166] ones involving abuse and neglect.

136. Maatua Whāngai went through a number of evolutions and shifts in focus. While these shifts appeared to offer a greater degree of tino rangatiratanga to Māori, Maatua Whāngai remained a programme with the State maintaining power and control.[167] Ultimately, inadequate investment by the State and the overly bureaucratic processes meant the programme was not sustainable.[168] Maatua Whāngai ended in 1992.

Ngā wharenoho mō ngā tama me ngā kōtiro me ngā pūnaha manatika taiohi

Boys’ and girls’ homes and youth justice institutions

137. Social welfare institutions which included State and faith-based care facilities like boys’ and girls’ homes and youth justice institutions, were often used as a way of curbing delinquent behaviour, and often the decision to place a child was made pre-emptively to reduce the risk of ‘dysfunctional’ behaviour developing. In 1975, Principal MP Doolan described Holdsworth School as “not offences orientated”:

“Holdsworth provides social behavioural and educational training which aims at returning boys to the community with a reduced probability of chronic dysfunction. [Residents] exhibit a pattern of behaviour which, if it continues, is likely to result in offences or personality maladjustment.”[169]

138. Tā Kim Workman described the admission criteria policy for social welfare institutions as indiscriminate. He explained that the boys were sent there for a variety of reasons, some were minor offenders, while others were sent there for more serious crimes. No attempt was made to distinguish them or address their individual needs.[170] As discussed in Part 2, some children and young people were admitted on the basis of protection.

139. Some social welfare institutions were just intended for short visits while others were for longer stays and focused on correctional training. However, as numbers began to grow, the care and protection and youth justice populations mixed more and more, with serious ramifications. Tā Kim Workman said that indiscriminate admissions and mixing made some boys and girls vulnerable to violence and the conditions “were almost guaranteed to turn vulnerable children and youth into scarred, distrusting and sometimes dangerous adults”.[171]

140. Older children were much more likely to be placed into youth justice institutions. For instance, in 1984, 22 percent of 9-year-old State wards were placed in youth justice institutions, the proportion increased to 47 percent for 14 year olds. As children aged, fewer foster placements were available as foster parents often preferred young children, which increased the likelihood of older children and young people being placed into social welfare institutions.[172]

141. Pressure on the system caused by the growth in the State ward population drove an increase in both the real numbers and the proportion of State wards living in youth justice institutions from the 1960s.

142. By the late 1970s, the social welfare institution system was under scrutiny and widely acknowledged as being in a state of crisis through a series of well-publicised inquiries and investigations.[173] By the mid-1980s, the Department of Social Welfare was making plans to close its social welfare institutions, in response to criticism from both individuals and organisations about the treatment of State wards and the living conditions.[174] These social welfare institutions were often places of extreme abuse, where violence became normalised.

143. By 1989, only a third of the national bed capacity in social welfare institutions was being used with resources being redirected to community-based alternatives.[175] Following the introduction of the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, the use of social welfare institutional care facilities dropped further.[176] Even more than its predecessors, this Act stressed family placements as the best option for children and young people, with social welfare institutions to be considered only as a last resort.[177]

144. Despite these changes, tamariki and rangatahi Māori continued to be the majority of those placed into social welfare institutions during the Inquiry period.[178]

Ngā pūnaha taurima kiritoru me ngā taurima ā-whakapono

Third-party care providers including faith-based care

145. As part of being placed in social welfare institutions run by the State, children and young people also experienced youth justice placements into indirect State care providers (also known as third party care providers) such as Moerangi Treks, Eastland Youth Rescue Trust and Te Whakapakari Youth Trust as provided for under section 396 of the Children, Young Persons and their Families Act 1989. Children and young people were sent to these facilities as an alternative to being placed into other youth justice settings. Some facilities were described as ‘boot camp’ style institutions due to the regimented and often harsh corrective training programmes and the poor living conditions. The Inquiry’s case study on Te Whakapakari Youth Programme, Boot Camp, discusses this further.

146. Cooper Legal, which represents survivors who were abused in third-party care provider facilities, described the State’s reliance on these facilities for those who were ‘difficult to place’:

“The approval scheme and the ability to provide care or programmes for children in a particular area, or in accordance with a particular kaupapa, gave rise to a plethora of programmes and organisations, often set up as small incorporated societies and completely reliant on the funding provided by CYFS [Child, Youth and Family Service].

“Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, a number of programmes were utilised by CYFS for young people, in particular young Māori men, who were regarded as too difficult to place anywhere else. These programmes had common traits. They were often run by a single charismatic man, who had total control over the organisation. They were often in remote places and were not regularly visited or monitored by CYFS”.[179]

147. Third-party care providers are examined further in the Inquiry's interim report, Stolen Lives, Marked Souls, which investigates the Hebron Trust, a faith-based youth residential facility registered under the section 396 Approval Scheme.

148. Children and young people were also placed into faith-based care homes.[180] Faith-based care settings provided an alternative option when State-run social welfare institutions became full, particularly at the height of institutional care in the 1970s.[181] This is discussed in more detail in the following chapter.

Ngā ara ki waenga i ētahi taurima tokoora

Pathways between multiple social welfare care settings

149. For those who spent extended periods in social welfare or faith-based care, multiple placements were common.[182]

150. Professor Elizabeth Stanley described how children and young people often progressed along a continuum of care placements.[183] Of the 105 participants in her study, 42 had lived in three or more different institutions, and many were discharged and re-admitted to the same institution multiple times.[184] Some of the 1,103 individuals who engaged with the 2015 Confidential Listening and Assistance Service, had experienced 40 or more placements during their time as a State ward.[185]

151. Extreme overcrowding and resourcing pressures on social welfare care settings during the 1970s and 1980s increased the amount of movement for children and young people.[186] Given their disproportionate representation in social welfare care settings, tamariki and rangatahi Māori were disproportionately affected by this unstable and harmful, ‘revolving door’ experience.[187]

152. Much like perceived delinquency and ‘challenging’ behaviour was a reason for children and young people entering social welfare care settings, it was also a reason given for moving children across care facilities. Survivors explained that their behaviour, which could prompt entry into a new, more ‘secure’ care placement, was often influenced by trauma experienced before entering, and / or while in care. NZ European survivor, Shaun Todd told the Inquiry he attempted take his own life because of the sexual abuse he was experiencing in Hamilton Boys’ Home, and he was taken to Waikato Hospital before being sent to Tokanui Psychiatric Hospital located near Te Awamutu.[188]

Ngā ara ki ētahi wāhi whakamau me ngā wāhi whiu

Pathways into more ‘secure’ settings, including correctional facilities

153. Running away from social welfare residences, often to find siblings, was a common behaviour that could also lead to children and young people being shifted, including to more ‘secure’ settings.[189] Survivor Mr GM told the Inquiry:

“I was constantly beaten in the [Weymouth] boys’ home. I was being bullied, the other boys would beat me and attack me for no reason. This went on for quite some time. I did not want to be there, so I ran away, as a result I was arrested. I was charged with absconding. I was put in a more secure facility [Day Street in Hamilton] so I wouldn’t escape.”[190]

154. The State placed some of its wards in long-term homes such as Holdsworth Boys' Home in Whanganui and Weymouth Boys' Home. Placement in these types of facilities were seen as a last resort when other social welfare institutions were unable to ‘control’ the escalating behaviours of a child or young person.[191]

155. NZ European survivor Alan Nixon experienced multiple abusive placements as a State ward and these institutional environments became increasingly more ‘secure’. Alan entered foster care at 4 years old and was eventually sent to Invercargill Borstal when he was 16 years old:

“Even though I was still a State ward, Social Welfare just left me in borstal, without any monitoring. They had no idea what to do with me and they just waited until I was too old to be their problem. I was sent back to my mother’s house on probation in April 1978 and I was discharged from being a State ward a few months later. I was back in borstal in November 1978, aged 17.

The next 20 years of my life was spent going in and out of borstal, prison, psychiatric hospitals and rehabilitation centres.”[192]

156. Survivors also told the Inquiry that the State also transferred children and young people to youth justice institutions, including borstals, when the social welfare residence they were placed in found them too difficult to manage.[193]

157. There were high rates of readmission, often into the same youth justice institution multiple times.[194] Perhaps reflecting the desperation many State wards felt while in social welfare settings, the Inquiry heard from survivors that one way to be discharged from State care was to “commit a crime serious enough to go to the Magistrate's Court”. Pākehā survivor Lindsay Eddy told the Inquiry:

“Once you go to court, you're in the probation service under the justice system and no longer a ward of the State, so you're treated better. That's how I ended up in Rolleston Detention Centre.”[195]

158. This same notion was reported in the 1982 Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Taitoko Levin’s Annual Report by Principal PT Woulfe where he stated that some boys at Kohitere believed:

“If they abscond from Kohitere often enough and create an extensive offending history, eventually they will be referred through to the District Court … for some, serving a three-month sentence of corrective training is seen as being more desirable than a normal nine to 10-month period at Kohitere.”[196]

159. These survivors inevitably spent more time in the care of NZ Police as they would be picked up after running away or transferred by NZ Police into these ‘secure’ settings. Pākehā survivor Beverley Wardle-Jackson was placed in Fareham House for girls in Pae-Tū-Mōkai Featherston after running away with a friend, only to be picked up by police officers. Her friend was transferred to Oakley Hospital in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, while Beverley spent that night in a police cell, was then taken to Mt Eden Prison and transferred to Oakley as well.[197]

I tino kitea ngā whakanohonga taupoto, huhua anō hoki ki ngā whare taurima

Interim and multiple placements in foster care were common

160. Children and young people could be placed temporarily in facilities like Ōwairaka and Wesleydale Boys' Homes in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland before being placed into foster care. These were short to medium-term social welfare residences,[198] typically for older children and young people who had committed offences or had more severe behavioural challenges, but also housed State wards awaiting placement. This included younger children needing foster care, who may have been removed from home due to welfare concerns, placed in these institutions. In these residences, young children were mixing with older children and young people with youth justice involvement.

161. Multiple placements in foster care were particularly common.[199] In 1968, at 2 years old, survivor Steven Long was placed into foster care by the State:

“I kept being moved to different homes. I was in six or seven different foster homes between April 1968 and July 1968. I was moved into another foster home in 1969, and then another one, before I was even four years old. This was the start of Child Welfare moving me from pillar to post, never knowing where to put me.”[200]

162. Often foster home breakdowns occurred because foster parents were inadequately supported by the State and could no longer cope.[201] Children whose placements in foster care broke down could be transferred into social welfare institutions or faith-based care settings.[202] NZ European survivor Charlene Montgomery moved through seven foster homes before she was 14 months old, before being placed in a faith-run children’s home:

“I had to leave each foster home for different reasons: the foster parents would break up, or they found it hard to look after us, or we had health issues. Some of the reasons for giving us up were quite ridiculous – in one home, they sent me away because I had worms.”[203]

Mai i te taurima tokoora ki ngā whare wairangi

Social welfare care to psychiatric care

163. The State sometimes transferred children and young people from social welfare care into psychiatric care settings. This was in response to actual or perceived mental, emotional, and/or behavioural issues. Sometimes this was for short periods of observation.[204]

164. In the late 1960s between 20 and 30 percent of girls discharged from Fareham House in Pae-Tū-Mōkai Featherston were transferred directly to psychiatric hospitals.[205] Admissions of girls into psychiatric care were often influenced by gendered discrimination, including being demonised for not living up to societal expectations of girlhood and womanhood. This is discussed further in Chapter 4.

165. By the 1970s, some social welfare residences had regular visits from psychological services, which could prompt assessment, referrals, and transfer of children and young people to other psychiatric or psychopaedic settings such as hospitals.[206] A 2006 Ministry of Social Development report, Social Welfare Residential Care (1950-1994) examined the departmental and institutional practices in social welfare residences. This report noted a small but significant group of children and young people in social welfare residences that had either come from, or went on to, a psychiatric hospital.[207] Examples given of this connection between institutions included: Hokio Beach School near Taitoko Levin, Holdsworth Boys’ Home in Whanganui and Lake Alice Child and Adolescent Unit; Allendale Girls’ Home in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and the psychiatric ward at Auckland Hospital; and Kimberley Boys’ Training Centre in Taitoko Levin, Epuni Boys’ Home in Te Awa Kairanga ki Tai Lower Hutt, Miramar Girls’ Home in Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington and Porirua Hospital.[208]

166. As discussed in the Inquiry’s interim report, Beautiful Children: Inquiry into the Lake Alice Child and Adolescent Unit, the Inquiry found the Department of Social Welfare paid insufficient attention to whether it had lawful authority to consent to the informal admission of children and young people to a psychiatric hospital.[209]

167. Survivors believed they were sometimes admitted from social welfare residences to nearby psychiatric or psychopaedic settings as punishment for unwanted behaviour, especially running away.[210] Survivor Alan Nixon, who had been running away, was sent to Lake Alice and placed into the adolescent ward from Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre in Taitoko Levin for observation while he was a State ward at 16 years old. Alan told the Inquiry he received ‘two jolts‘ of electric shocks without muscle relaxant or anaesthetic “as punishment for not telling the Lake Alice staff the reasons why I kept running away”.[211]

168. After a month at Lake Alice, where he experienced further abuse and neglect, Alan was sent back to Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre.[212]

169. Survivors who have experienced multiple entries from social welfare into psychiatric and psychopaedic settings over their life described feeling like they were labelled by the mental health system. Survivors felt that their mental health record increased their likelihood of being recommitted into psychiatric and psychopaedic institutions.[213] Pacific survivor Rachael Umaga, who was admitted to psychiatric institutions voluntarily and formally more than 10 times, said: