Chapter 1: Context and history

Van Asch College

8. The Education Act 1877 made education compulsory for all Pākehā children between the ages of 5 and 14 years old. Although handicapped children (wording of the time) were exempt from school attendance, they were not specifically excluded from education. In 1878, Christchurch politician William Rolleston was instrumental in advocating for the Government to set up and fund a deaf school.[5] At the time, parents had to either provide private tuition or send their children to a deaf school in Australia. Rolleston thought this was wrong.

9. Sumner Institution for the Deaf and Dumb (later named Sumner School for the Deaf and then renamed Van Asch College in 1980). Sumner Institution for the Deaf and Dumb was one of the first State schools in the world providing education for Deaf children. The school was established in Sumner, a seaside suburb of Ōtautahi, Christchurch. The school was initially a residential school and opened with five people, which quickly increased to 10 people by June 1880.[6] By 1891 the school had 21 people aged between 6 and 19 years old.[7]

10. Gerrit van Asch was appointed the first director of the school because of his training and experience teaching the oral method in Europe, which the New Zealand Government saw as the modern approach to Deaf education. The State’s early adoption of that approach was endorsed at the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf (commonly referred to as the Milan Conference) in September 1880, where an international congress of Deaf educators declared the oral method to be the superior method for Deaf education and passed a resolution banning the use of Sign Language in schools.[8] The school (later renamed Van Asch College) adopted the oral method for Deaf education six months before the Milan Conference.

11. Gerrit van Asch was known as a strict teacher and taught the new entrants himself to ensure they didn’t sign. He used corporal punishment to enforce discipline at the school, and the practices of oralism and corporal punishment continued after his retirement in 1906.

12. Compulsory education was extended to Māori children by the School Attendance Act 1901, which along with subsequent amendments stated that it was the duty of parents of Deaf children to provide “efficient and suitable” education between the ages of 7 and 16 years old. Parents who could not do so were obliged to send their children to an institution decided by the Minister of Education. It is unknown whether the mandate to attend deaf schools was applied in practice to tāngata Turi Māori, but the wording of the Act applied to all children.

13. Herbert Pickering was appointed principal in 1940 and was in the role until he died in 1973. He was instrumental in establishing deaf schools in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland from 1942 to accommodate North Island pupils during the Second World War, and in establishing units attached to mainstream schools from the 1950s.

14. The roll increased significantly from 126 in 1943 to 175 in 1944 due to the impact of a rubella epidemic in 1939.[9] By 1945, 215 people were enrolled at Van Asch.[10] In 1946, there were 143 people at Van Asch and 90 percent were boarders.[11]

15. Numbers declined[12] until two epidemics of maternal rubella in the 1960s again swelled enrolment numbers. Reports from Van Asch school principals noted the difficulty in planning for capacity as the numbers of Deaf infants rose and fell with waves of epidemics, especially maternal rubella, which was thought to account for half of hearing loss in the 1960s.

16. An inspection report by the Department of Education in 1952 reflected the strong emphasis on learning to speak and lipread at Van Asch:

“In the playing fields as well as in the classrooms, they display a natural willingness to express themselves in speech, while in the upper rooms, lipreading reaches a high degree of proficiency. Comparison with previous inspection visits indicates that a pleasing measure of success is attending the efforts to promote the quality of naturalness in speech, an important consideration in ensuring easy and intelligible oral intercourse with those who hear.”[13]

17. In 1962, Māori enrolments comprised 10 percent of the school roll. A 1991 Ministry of Education report on Van Asch noted of the 73 people on campus, six were Māori (8 percent), and three were noted to be of ‘other’ ethnicity (4 percent). Two reports from Van Asch in 1974 and 1975 noted that ‘Polynesian’ people made up 8 percent and 11 percent respectively of the school roll. ‘Polynesian’ was not defined.

18. Herbert Pickering introduced initiatives to reduce the number of people who had to board away from home, recognising that children should be with their families. He noted that in 1973, 169 children and young people would attend Department of Education unit classes attached to mainstream schools in their hometown and could have a normal home life. He reported that 31 families had moved to Ōtautahi Christchurch so their children could be day pupils, following his long-held policy to encourage children and young people to have a normal home life.

Kelston School for the Deaf

19. Kelston School for the Deaf (Kelston) was established in 1958 in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, replacing temporary State schools for the Deaf at Mount Wellington and Titirangi (Lopdell House), which were established from 1942. Like Van Asch, Kelston followed the oralist method of education.

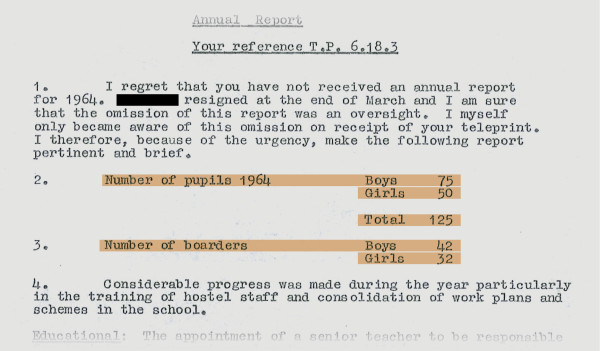

20. During the 1960s enrolment numbers grew and ranged from 125[14] in 1964 to 279 by 1969[15], with boarding numbers increasing from 74 to 115 across that period. Boys outnumbered girls both at the school and as boarders.[JW1]

21. The principal of Kelston noted in his annual report for 1968 that a greater proportion of boarders came from underprivileged backgrounds and most of them had “little or no effective home training before coming to school”.[16] It seems likely that as boarding numbers declined, children from disadvantaged backgrounds may not have received an adequate education.

22. The school had a high proportion of Māori and Pacific children and young people. In 1974, 35 percent of people at Kelston were recorded as ‘Polynesian’.[17] As with Van Asch, ‘Polynesian’ was not defined.

23. Enrolments at Kelston in the 1970s declined from 218 in 1970[18] to 102 in 1979.[19] Boarding numbers declined significantly from 108 to 14 across the same period.

24. In 1979, Van Asch and Kelston moved away from oralism with the introduction of Total Communication, an artificial form of communication that combines spoken English with signing, with some teachers using Australian Signed English.

25. A 1994 Education Review Office (ERO) report noted that there were 162 children and young people at Kelston – 56 percent were boys and 44 percent were girls. Although limited ethnicity records were available for the Inquiry period, the ERO report noted that 28 percent of were Māori, 27 percent were Pākehā, 31 percent were Pacific Island, 10 percent were Asian and 4 percent were recorded as ‘Other’.[20]

26. The 2005 Kelston Annual Report noted that 23 children and young people were in residence and that 36 percent were European, 54 percent were Māori, 5 percent were Asian and 5 percent were Pacific Island.[21]

27. The 2010 Kelston Annual Report noted 14 students were in residence with ethnicity recorded as 21 percent European, 30 percent Māori, 21 percent Pacific Island, 14 percent Asian and 14 percent African.[22]

28. Participants in a study who attended Van Asch and Kelston during the 1950s to the1970s reported that a high proportion of pupils were Māori. However, despite the large Māori peer group, school was a monocultural, Pākehā environment.[23] The high proportion of Māori students at Kelston may have been due to poor Māori health access and outcomes during outbreaks of rubella, meningitis and measles, which were known causes of deafness.[24]

Ko Taku Reo

29. In 2020, Van Asch and Kelston were combined into one national organisation called Ko Taku Reo – Deaf Education New Zealand. Examples of Ko Taku Reo’s approach to Deaf education includes teaching and embracing Sign Language, developing a Deaf studies curriculum and bringing children from mainstream education to Ko Taku Reo’s residential hui.

30. At the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing held in July 2022, Ko Taku Reo Board Chair Dr Denise Powell acknowledged that it had failed survivors: “I want to begin by acknowledging the many hundreds of survivors of abuse in care who have shared their stories and experiences with this Royal Commission of Inquiry, and in particular, those who have experienced abuse while in our care, Deaf Education. I acknowledge your whānau, your friends, the many people who have supported and listened to you over the years when our institutions failed you.”[25]

31. Dr Powell said that the Milan Conference marked the beginning of global language deprivation for the Deaf community and sadly Aotearoa New Zealand became a world leader in oralism, which prevailed for more than 100 years.[26] Dr Powell further acknowledged the disproportionate impact on Māori: “At the same time Māori communities were experiencing similar loss of language, identity, and mana through rapid colonisation and loss of land and resources. For those of us who are hearing and Pākehā, it’s difficult to imagine the effects of this double marginalisation on Turi / Deaf Māori.”[27]

32. Dr Powell delivered an apology to all survivors of Van Asch and Kelston on behalf of Ko Taku Reo: “As the kaitiaki of Deaf Education in New Zealand, today we say we are sorry. We are sorry that you were not given a language, your birth right to learn and use and own as part of your identity. We are sorry for the physical violence and harm that you endured. We are sorry for the sexual abuse that you endured. We are sorry for the emotional and psychological damage and trauma that you endured.”[28]

Van Asch & Kelston Timeline

- 10 March 1880 Sumner Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, later renamed Van Asch College in 1980 (Van Asch), opened with five children and young people, which quickly increased to 10 by June 1880.

- September 1880 Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf (Milan Conference), passed a resolution banning the use of Sign Language in schools. Sumner School adopted the oral method for Deaf education six months before the Conference.

- 1891 Van Asch school had 21 children and young people aged between 6 and 19 years old. Gerrit van Asch taught the new entrants himself to ensure they didn’t sign.

- 1940 Herbert Pickering was appointed principal of Van Asch in 1940 and was instrumental in establishing deaf schools in Auckland from 1942 to accommodate North Island pupils during World War II, and in establishing units attached to mainstream schools from the 1950s.

- 1943 – 1946 The roll increased significantly at Van Asch from 126 in 1943 to 175 in 1944 due to the impact of a rubella epidemic in 1939. By 1945, 215 children and young people were enrolled at Van Asch.[29] In 1946, there were 143 enrolled at Van Asch and 90 percent were boarders.

- 1952 An inspection report by the Department of Education reflected the strong emphasis on learning to speak and lipread at Van Asch.

- 1958 Kelston was established in Auckland, replacing temporary State schools for the Deaf at Mount Wellington and Titirangi (Lopdell House), which were established from 1942. Kelston also followed the oralist method of education.

- 1959 The Department of Education’s Director of Education Clarence Beeby acknowledged that residential care may have been harmful to Deaf children and young people.

- 1960s Numbers grew at Kelston and ranged from 125 in 1964 to 279 by 1969, with boarding numbers increasing from 74 to 115 across that period. The principal of Kelston noted in his annual report for 1968 that a greater proportion of boarding students came from underprivileged backgrounds.

- 1962 Some Deaf children were brought from the Pacific Islands to be educated at Kelston.

- 1966 Van Asch Principal said in 1966: “Educational retardation is a natural consequence of deafness and it is rare for our pupils to achieve academic success.”

- 1970 – 79 The numbers at Kelston in the 1970s declined from 218 in 1970 to 102 in 1979. Boarding numbers reducing from 108 to 14 across the same period.

- 1974 In 1974, 35 percent of those enrolled at Kelston and 8 per cent at Van Asch were recorded as ‘Polynesian’. ‘Polynesian’ was not defined.

- 1979 The schools moved away from oralism with the introduction of Total Communication, an artificial form of communication that combines spoken English with signing, with some teachers using Australian Signed English.

- 1983 Department of Education inspection report for Van Asch noted its curriculum was different to mainstream schools.

- 1994 ERO report for Kelston stated that the school had no school-wide information on individual achievement, and this should be addressed by the school.

- 1994 Up until 1994, neither of the deaf schools had a documented complaints procedure.

- 2000 An ERO report for Kelston noted that the board needed to “urgently develop documentation to guide the operation of the residential area to ensure the safety of children, young people and staff”.

- 2020 Van Asch and Kelston were combined into one national organisation called Ko Taku Reo – Deaf Education New Zealand. Examples of Ko Taku Reo’s approach to Deaf education includes teaching and embracing Sign Language, developing a Deaf studies curriculum and bringing children from mainstream education to Ko Taku Reo’s residential hui.

- July 2022 At the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing, Ko Taku Reo Board Chair, Dr Denise Powell, acknowledged that it had failed survivors and offered an apology.

Footnotes

[5] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, pages 17–19).

[6] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 27).

[7] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 34).

[8] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 36).

[9] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, pages 141–142).

[10] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 143).

[11] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 188).

[12] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 171).

[13] Education Department, Inspection report: Sumner School for the Deaf (September 1952, page 2).

[14] Kelston School for the Deaf, Annual Report (15 April 1965, page 1).

[15] Kelston School for the Deaf, Annual Report (22 December 1969, page 1).

[16] Kelston School for the Deaf, Annual Report (7 February 1969, page 3).

[17] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 211).

[18] Kelston School for the Deaf, Annual Report (11 February 1971, page 1).

[19] Kelston School for the Deaf, Annual Report (18 December 1979, page 7).

[20] Education Review Office, Confirmed effectiveness review report for Kelston Deaf Education Centre (7 October 1994, page 1).

[21] Kelston School for the Deaf, Annual Report 2005 (10 May 2006, page 31).

[22] Kelston School for the Deaf, Annual Report 2010 (25 May 2011, page 35).

[23] Smiler, K and McKee, RL, “Perceptions of Māori deaf identity in New Zealand,” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 12(1), (2007, page 99).

[24] Witness statement of Stephanie Awheto (26 October 2022, para 49).

[25] Transcript of opening statement of Ko Taku Reo at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 July 2022, page 443).

[26] Transcript of opening statement of Ko Taku Reo at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing ( Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 July 2022, page 444).

[27] Transcript of opening statement of Ko Take Reo at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing ( Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 July 2022, page 444).

[28] Transcript of opening statement of Ko Take Reo at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing ( Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 July 2022, page 445).

[29] Stewart, PA, To turn the key: The history of deaf education in New Zealand, Master’s Thesis, University of Otago (10 December 1982, page 143).